Who among us has not secretly wished to do all the drugs with zero of the addictive consequences?

Wait, maybe don’t answer that. Because that’s not exactly what scientists at the University of British Columbia set out to do when they genetically engineered mice that show no signs of addiction, even after repeated injections of cocaine.

Videos by VICE

In fact, lead researcher Shernaz Bamji told VICE her team was aiming to create the opposite—a mouse brain with amplified addiction tendencies. Yet Bamji ended up with a bunch of party-hardened rodents that apparently don’t get thirsty for their next hit.

The UBC study, published this week in Nature Neuroscience, shines new light on what part of addiction is learned, and what is genetic. It also adds to a long and storied history of getting mice fucked up in the name of science.

For the purposes of this article, let’s say that “learning” is an unequivocally bad thing. The only skill we’re talking about learning here is how to become a sad and broken character from Requiem for a Dream. Bamji explains why: “Researchers nowadays think addiction is just learning gone haywire in a particular part of the brain,” she told VICE.

Part of that “learning” has to do with a group of proteins called cadherins. Bamji says cadherin acts like glue, strengthening connections between brain cells.

“To learn something you have to strengthen these synaptic connections. When you add more glue to the synapse, you cause it to get stronger,” she said.

Read more: Sex, Drugs and Music Are All Related in Your Brain

Past research has shown that people with addiction issues tend to have genetic mutations that produce extra “glue” in the brain’s addiction-associated reward circuitry. This is the area where certain kinds of wiring can make people act like assholes, or even lose the ability to function in search of one more dopamine boost.

Again, Bamji wanted to encourage bad habits in some mice. “We genetically engineered animals to have lots of cadherin glue at these synapses. We thought more glue, stronger synapses, more learning, more addiction. But we saw exactly the opposite.”

All of the mice were injected with coke and saline on alternating days. The narcotics were consistently delivered in part of a cage with recognizable setting markers. Then the mice were left to roam as they please.

The normie mice had zero chill and made a beeline for the spot where they last picked up. “Normal animals, when you let them walk around, they’ll always gravitate to the chamber where they receive the drug, which indicates they’re looking for that high,” Bamji said.

The mice with extra cadherin, meanwhile, didn’t seem to get the memo. This was a significant and surprise finding, according to Bamji.

The researchers ultimately found that too much glue actually stopped new brain connections from forming. “It’s kind of like a traffic jam. Basically, you can’t get the right kind of neurotransmitter receptors to the membrane, so you don’t get learning—no synapse strengthening, no learning, no addiction.”

Of course, it’s not yet clear whether the mutant mice were actually feeling the effects of the drug, or if they were genetically engineered to be pleasure-hating squares.

“We can’t interview the animals to determine which it is,” Bamji told VICE. “Either it’s just not learning that this is the place where I got that yummy high, or the animal is really not feeling that high—we’re not totally sure.”

What we can say is that our genes may have more to do with our drug habits than previously thought. Down the road, we may be able to test for genetic markers in humans that are prone to addiction.

But Bamji says we shouldn’t rule out personal choices or environmental factors, either. Besides, she’s not going to be engineering an addiction-resistant human brain anytime soon.

Follow Sarah Berman on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Zootopia 2 -

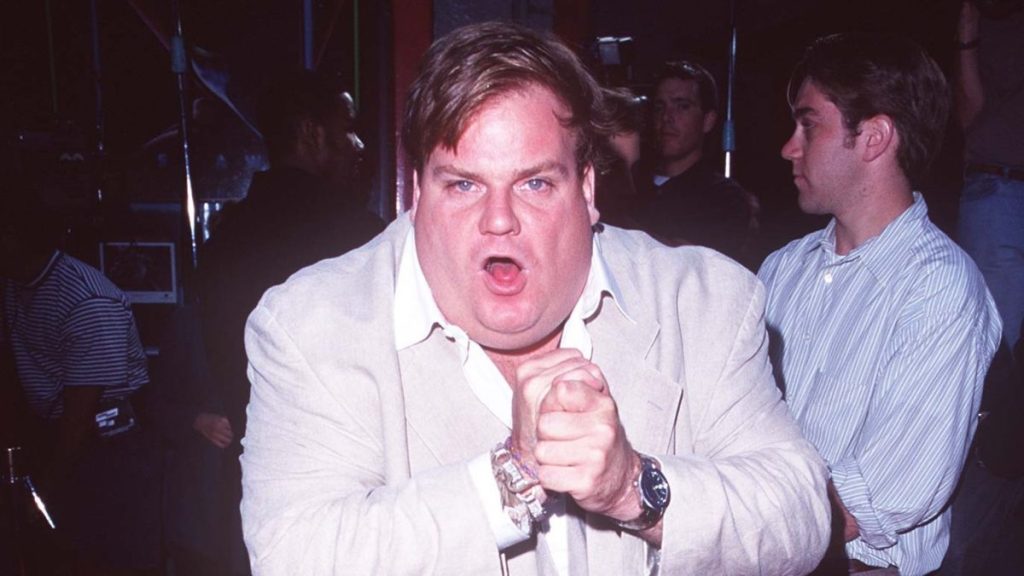

Chris Farley (Photo by SGranitz/WireImage) -

John Belushi (Photo by Michael Gold/Getty Images) -

All Pictures by Ashton Hertz