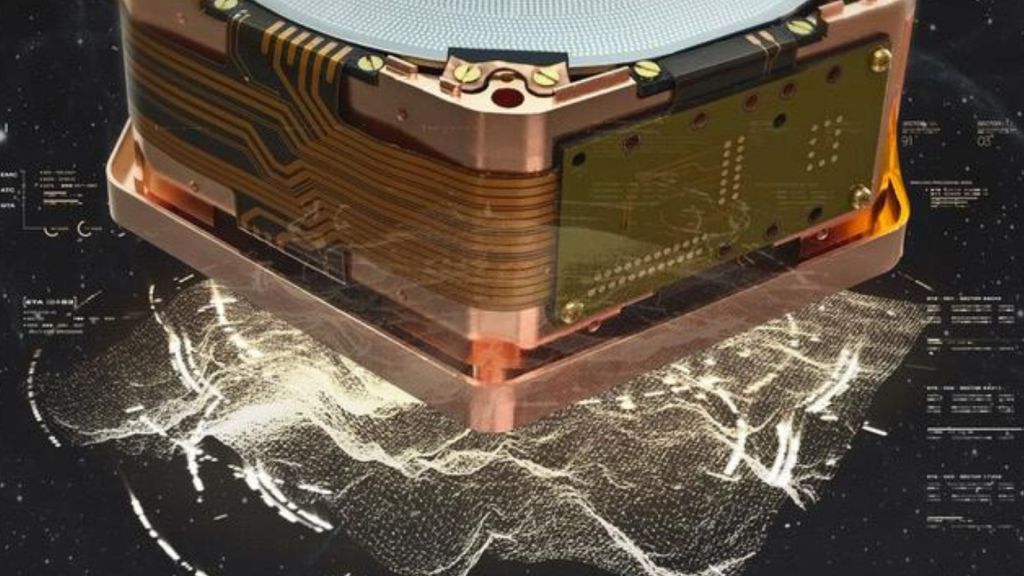

A new study has found that radiation including cosmic rays are causing errors in quantum computers’ calculations, solving a decades-old mystery about the origin of these issues, known as quasiparticle poisoning.

Researchers from MIT and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory determined that environmental radiation—including beta particles, gamma rays, and X-rays—break apart bonded electrons, which then disrupt qubits. Their study was published on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Videos by VICE

“If you look back at the last few years of quantum computing development, it’s been improving exponentially,” said Ben Loer, a staff physicist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and a co-author of the study. “All we’ve done is found one more place where it needs to be improved, but we have plenty of ideas on how to do it.”

The basic unit of information in traditional computing is a bit, which can store a 1 or a 0. Quantum computing derives its power from qubits, basic units of information that have the ability to store two states at once. A main challenge in achieving practical quantum computing is improving coherence, or the length of time that a qubit can retain its quantum state—the longer you leave a qubit, the likelier it is to be disrupted by quasiparticles, which are unpaired electrons.

Radiation can originate on Earth or from outer space. Building materials like concrete and brick emit low levels of radiation, and extraterrestrial nuclei produce cosmic radiation when they interact with Earth’s atmosphere. The research team found that without intervention, cosmic and environmental radiation alone would limit the lifespan of a qubit to a few milliseconds. Qubits today last shorter than a thousandth of a millisecond, so solving the radiation problem is crucial to one day achieving practical quantum computing.

A chance encounter inspired the study when Pacific Northwest National Laboratory nuclear physicist Brent VanDevender needed to borrow equipment for an experiment from William Oliver, a quantum information researcher. In the course of lending the equipment, Oliver mentioned that quantum computing had long been puzzled by greater-than-expected amounts of quasiparticles, adding that environmental radiation was an emerging hypothesis.

“Neutrino physicists and dark matter physicists deal with mitigating the effects of radiation all the time—it’s one of the hardest parts of our life,” VanDevender said. “It was really natural for us to work with Will Oliver to test that hypothesis, which is what the paper is about.”

In the paper, the authors also propose and test a solution for the radiation in the form of a lead shield, which is commonly used in nuclear and particle physics. They made a shield from 10-cm-thick lead bricks and placed it around a cryostat that keeps the qubits at a low temperature, finding that it mitigated some of the effects of the radiation.

Implementing the change was straightforward, but it was much more challenging to measure its effect, VanDevender said.

“Building the pile of bricks was easy—they sent in a grad student and he hauled them up—but making the actual measurement that demonstrated that the bricks actually had some effect on the qubit, that was a very subtle, small signal,” he said.

That’s because the qubits produced today can only maintain quantum states for microseconds, so measuring any change in their longevity is a tedious effort.

It might seem obvious in hindsight to some that cosmic radiation caused an excess of quasiparticles observed universally, but Loer and VanDevender said that they were met with pushback when presenting the group’s hypothesis.

“After the fact, when we said, ‘We’ve demonstrated that radiation is a source of excess quasiparticles,’ everyone said, ‘Well yeah, that’s obvious,’” Loer said. “But those same people six months earlier—it hadn’t seemed to occur to anybody.”

This may have been because some of the materials they used were commonplace to nuclear physics but not readily available to a quantum information researcher, VanDevender said. For example, he has lead bricks “all over” his nuclear physics lab, but someone who studies qubits would have no reason to stock them, let alone know where to find them.

VanDevender said that future work is in order to determine how each form of radiation affects quasiparticle formation, though the group hypothesizes that each type will have its own, unique effect. There’s also the theoretical question of how high-energy radiation somehow breaks very cold electron pairs into quasiparticles.

Not only can the group’s findings help make better quantum computers; the applications of this research come full circle to inform VanDevender’s and Loer’s physics research.

“As it turns out, the same physics which makes radiation a nuisance for qubits means that something like them should be very good detectors,” VanDevender said. “For Ben and me, searching for dark matter or really rare neutrino interactions, we’re sure there are detector technologies to be added that will extend our discovery reach.”

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Allen Berezovsky/Getty Images) -

Alessandro Bremec/NurPhoto via Getty Images -

Photo: Elena Medvedeva / Getty Images -

Photo: Maria Korneeva / Getty Images