If there’s a single meme that encompasses the prevailing feeling of 2020, seven months into a global pandemic and with less than three weeks until a crucial American election, it’s the cartoon dog sitting in a room on fire, next to a speech bubble that says, “This is fine.” The New York Times called this the meme of the year back in 2016, yet its appeal is timeless as the flames continue to engulf us.

People have a lot to say about 2020, and most of it is bad. The memes are darker and more defeated, and Twitter has devolved into a watering hole for a sense of shared doom (often in the form of subtweets and snipes). The anxiety comes from all sides: health concerns, climate change, divisive politics, money issues, lost jobs, family strife, and so on. It’s rare to see anyone say outright that life is good—”fine,” maybe, in the dog in a burning room sense, but rarely “good,” without disclaimers.

Videos by VICE

For the past 26 years, Bert Jacobs and his brother John have turned the “Life Is Good” mantra into a business. As of 2016, the Boston-based brand—which prints shirts and other merchandise with the phrase, often accompanied by a grinning cartoon face—was on sale in approximately 4,500 stores, and pulling in $100 million in sales. The company’s approach is so well-known that its designs have been parodied: Life Is Crap offers the opposite sentiment for those tired of unceasing optimism.

Since its official launch in 1994, Life Is Good has weathered several crises in the United States, including 9/11, the Great Recession, and the Boston Marathon bombing. But this year has seen a deluge of objectively bad things: lockdowns and virus fears; more than 200,000 Americans dead from COVID-19; an unemployment crisis amid rising rent in many cities; continued police violence; politics polarized even further by the looming election. In June, the New York Times posed the suggestion that perhaps to cope with all this, we should consider becoming more pessimistic. It made me wonder: In a year filled with strife, when it might feel disingenuous to admit to happiness, what’s it like to sell the idea that life is good? And is anyone really buying it?

“It’s been a very interesting ride,” said Life Is Good co-founder Bert Jacobs, who clarified that his role as CEO stands for “chief executive optimist.” Growing up in a “very dysfunctional” home with two parents who dealt with depression in opposite ways—a father who coped with alcohol and yelling, and a mother who relied on music, dance, humor, and storytelling—Jacobs learned to use optimism as a tool for a “happy and fulfilling life,” and built a successful company with it. But like many companies, Life Is Good was hit hard by the pandemic.

With about half of its business relying on wholesale, and those orders canceled or postponed indefinitely as brick-and-mortar stores closed, “revenue kind of shot down to nothing.” The pressure of potential bankruptcy was the topic of several meetings, and the company’s owners discussed cutting staff and closing its New Hampshire distribution center over safety concerns.

But none of those things happened. To date, “we have had zero positive cases, and we have had zero layoffs,” Jacobs said. “It’s a strange year. It went from just knocking the wind out of us like everybody else, to all of a sudden being a really strong year. But moreover, it’s enabled us to shift the business model, and we’re building a fantastic plan for the next three, five years.” As it turns out, the business of optimism is booming.

The pandemic has offered an opportunity to identify and rework problematic systems, and retail supply chains are among those. Typically, these processes have relied on companies making projections for consumer behavior many months ahead of time and establishing inventory accordingly. (The country’s recent bicycle shortage, for example, was the result of the industry’s failure to predict the surge in demand.) In the past, Life Is Good would print an inventory of products predicting what people might want. But because nobody has a crystal ball to perfectly understand consumer behavior, whoever ended up with the excess merchandise took a hit; any remaining products had to be sold at a loss.

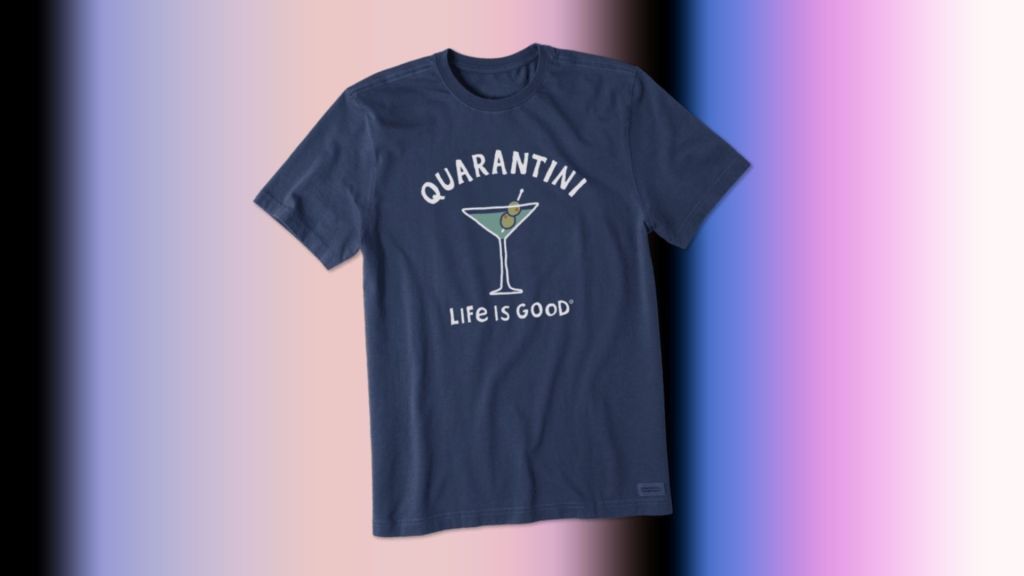

To break free from that system, Life Is Good had been preparing to shift to a print-to-order model before COVID hit, but once the pandemic was in full swing, the company pivoted entirely in the face of looming layoffs and bankruptcy. Jacobs and his team implemented new safety precautions allowing them to keep the New Hampshire facility open. There used to be a 12-to-18-month lag between designing a product and distributing it; that delay is now just two days. “So [we decided to] design on Monday what goes into the market on Tuesday, and see what happens,” Jacobs said. The change was a success—it met a public demand for immediate products with lighthearted yet relevant messages about staying healthy, social distancing, working from home, sports cancellations, and more. One fall-themed shirt says, “Namaste six feet away.”

Direct-to-consumer sales have replaced losses from wholesale, though that’s rebounding, too. Stores are bouncing back, gifts are up, and products for the virtual class of 2020 have been “blockbuster.” Though the company has grown at “a good pace” over the last few years, Jacob said, this year’s growth has been particularly sharp. Despite the outward pessimism of many social media users, with those platforms functioning as echo chambers of discontent, there’s clearly an excited market that still believes life is good—or at least wants the phrase printed on shirts and hats and face masks as a not-so-subtle reminder.

This wasn’t the first time that the company has found surprising success during not-so-good times. After 9/11 and the Boston Marathon bombing, the brand responded with designs that proved hugely popular. “We’ve noticed that during the most challenging times, our brand actually thrives,” Jacobs said. The current moment is no exception. To him, it’s not just that consumer behavior shifts on its own toward positive products, but that we’re now also inundated with bad news that can make people feel fed up, as though they can’t fix everything on their own. While products emblazoned with positive messages may feel corny to some, they can also help others. “You can take care of the people that you love, and you can try to bring some positive energy to the table, and that tends to be the community of people that gravitate to Life Is Good—and you know, thankfully for us, it’s a growing community.”

A T-shirt with a slogan of positivity won’t actually change the state of the world, but no matter where and how you find your own personal reminder, it’s nice to remember—even if the thought is fleeting—that life isn’t entirely bad. Sometimes, life can even be kind of good. Just read the shirt.

Follow Bettina Makalintal on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Gie Knaeps / Getty Images -

Screenshot: Microsoft -

Kevin Winter/Getty Images for The Recording Academy -