This spring, VICE partnered with Fotografiska New York to present New Visions , an exhibition showcasing 14 emerging photographers from around the world who are changing the way we see. To highlight the work beyond the museum, we asked 14 of our favorite, fresh voices in culture to respond to the photos in writing. Here, prolific art critic Rahel Aima profiles Beirut-based photographer Tamara Abdul Hadi. Read more from the New Visions series here, and learn how to visit the show at Fotografiska New York here.

The first thing you notice about photographer Tamara Abdul Hadi’s portraits of Arab men is their gentle sensuality. In her ongoing series Picture an a Arab Man, for instance, they are shot bare-chested against a white background, often with unbound hair and closed eyes, all wavy locks and splayed lashes and bristly stubble on smooth skin. Almost as if in a 1990s music video, the subjects lean forward or extend their necks so that only their faces are in focus. The resulting images showcase the ethnic diversity across the Arab world. At the same time, they do double duty in countering stereotypes—both of the violent would-be-jihadi promulgated by Western media post-9-11, and the region’s own expectations of societal machismo of toxic masculinity.

Videos by VICE

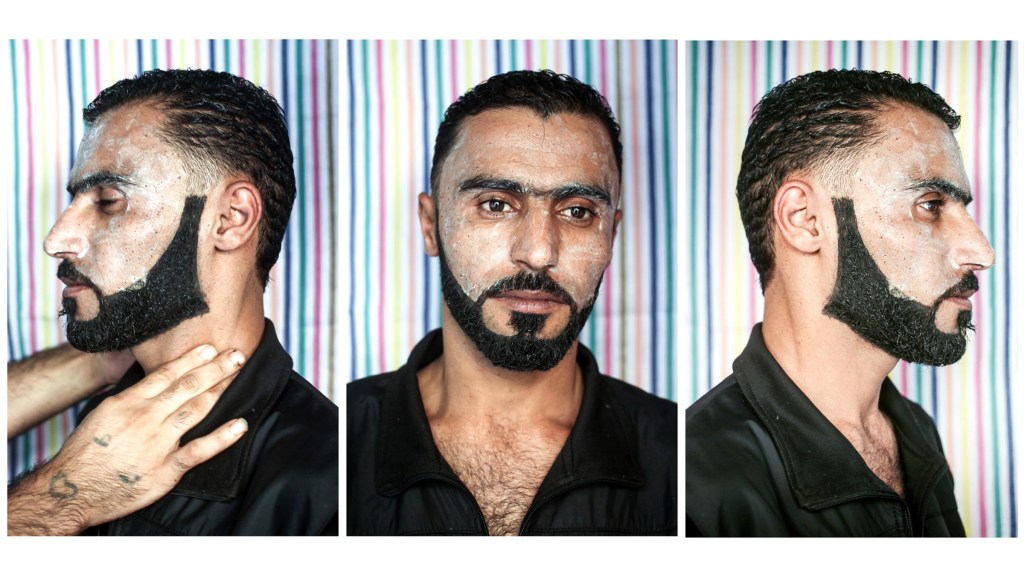

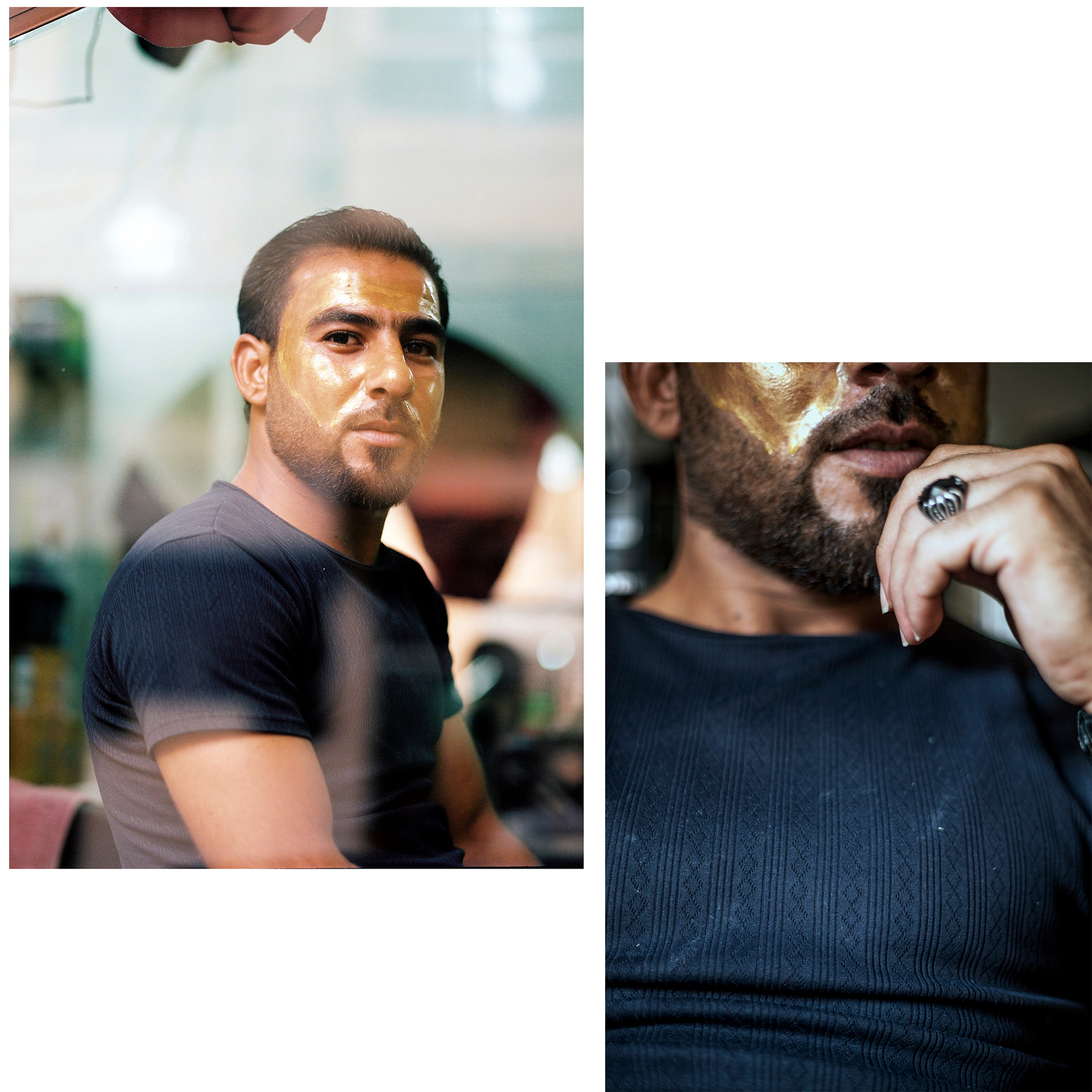

A similar intention and aesthetic underlies The People’s Salon, an offshoot of Abdul Hadi’s Arab Man series that documents barbering culture and male communal self-care in Lebanon and Palestine. In this series, we see close crops of earnest boys and men in front of colorful backgrounds sporting elaborate fades and glowing face masks of charcoal and gold. Here, too, eyes are often gazing into the distance or closed in the unworried bliss of spa time. When they do meet the lens, they are self-possessed, yet soft and relaxed. The images are permeated by a deep sense of security and comfort: with the photographer, in the salon environment—you get the sense that these are regular haunts where they feel at home—and in their own identity.

Like many artists from the Middle East, Abdul Hadi, who is currently based in Beirut, is invested in redressing stereotypes of Arab masculinity. In the work coming out of the region, she noticed an overwhelming focus on women, she said. So she shifted her lens toward Arab men, who are often documented as amorphous crowds but rarely as individuals. She’s been working on her Arab Man series since 2009, and hopes to turn it into a book. Along the way, she found herself especially fascinated by the “different and unique, amazing” haircuts that she saw, and the ways that trends differed based on place. That’s when she decided to hone in on salons.

The People’s Salon focuses on three barbershops, each located in working class or shaabi—”of the people”—neighborhoods in Gaza, Ramallah, and Beirut. They are both run by and primarily serve refugees and other displaced people, many of whom know each other from their homelands. Like the barber-dentist-surgeons of old, these shops provide more than just haircuts or beard trims: Their services include beard dyes, waxing, threading, golden facemasks, and all manner of facials. One such establishment, Tamer Shehadeh’s Salon Tamer, began as a little shop in the Qalandia refugee camp at the edge of Ramallah, before a business partnership allowed him to move out to the center of the city. (Its name has since been changed to Tamer’s Beauty Center to reflect this expanded scope of treatments.)

The Gaza barbershop, Salon Rimal, is run by second-generation barber Mohamad Bakir. He’s responsible for the follicles of most of the city’s soccer players, and hopes to bring Palestinian hairdressing to the world. In 2016, he released a historical encyclopedia of hairdressing in Gaza. Abdul Hadi hopes to compile this project into a book too, fashioned after those hairstyle inspiration books that used to be so prevalent in the ‘80s and ‘90s, at least in the UAE. (Growing up, I remember being bemused by the gravity-defying spikiness—not quite understanding the concept of hairspray—and later, chunky bleached streaks and immaculate loops of synthetic hair dyed an array of different colors.)

Like the Black barbershops U.S. audiences might be more familiar with, which themselves played a crucial role in promoting entrepreneurship following the abolition of slavery, these barbershops are important community hubs for recently-displaced clientele. “It’s a once a week refresher, they don’t go in fast,” Abdul Hadi explained. “They spend a little bit of time, they sit on the couch. You wait, you read, you talk, you eat, you drink coffee; it’s a whole process,” she said, adding that for these men, it’s very natural to get weekly facials or engage in these other aspects of self care. “You know, we’re not used to men taking care of their skin as much as women. So there’s something that I really loved and found inspiring [about that].”

Abdul Hadi was born in Abu Dhabi to Iraqi parents, grew up in Montreal, and moved back to the UAE, this time to Dubai, after getting a BFA. There, she became fascinated by the city’s population of migrant workers and took up photography—she’s entirely self-taught—going on to work as a stringer for Reuters. She’s lived in many cities around the Middle East, and was a cofounder of Rawiya, the region’s first all-female photography collective. But Abdul Hadi says her work isn’t about her. “I don’t know if I want to go deep into my background,” she said firmly. “I consider myself a social documentarian. And I’m interested in subjects that might be underrepresented, in subcultures.”

Abdul Hadi’s snapshot-like photographs follow this documentary ethos too, emphasizing the context and identity of the subject over more formal technical or aesthetic considerations. She rarely shoots in a studio, much preferring natural light. Here, she takes the protective capes worn by each customer when they finish their haircuts and uses them as backdrops “kind of mimicking a studio space, but not really.”

The images are remarkably colorful, boasting primary blues, yellows, and pinks in addition to the odd spacefoil silver or stripes. In other images from the series, the subject is shot wearing a hair-cutting cape, with a little bit of the salon visible in the background. “It’s nice to see both sides,” Abdul Hadi explains, in reference to the context provided by these shots. I think it changes the project.” Often, the client’s tops are matched with the sheets, as with the images of Abu Samar wrapped in a pink towel against a hot pink background. The tone-on tone effect emphasizes the lovely textural contrasts between the fuzzy towel and the impeccable, curvaceous comma of his fade.

“I’m not Lebanese, and I tend to connect with people that are outsiders,” Abdul Hadi explains, adding that the cuts in these salons are very different to what you might find in standard Beiruti joints. The third salon in her series, Beirut’s Salon Raqi, is run by displaced Syrian Abdel Atheem, whose specialty is a black beardscaping and dye combo. Abdul Hadi speculates that this is a throwback to Mesopotamian traditions where shiny, blackened beards were associated with power and royalty. Indeed, Atheem learnt his craft from an Iraqi barber. “They connect and work with and teach each other,” Abdul Hadi enthuses. “Barbers are really proud artists in a way, they’re really proud of their work. So it’s a very beautiful thing to see.”

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Francesco Castaldo/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images) -

M Scott Brauer/Bloomberg via Getty Images -

Firefly Aerospace/YouTube -

Justin Paget / Getty Images