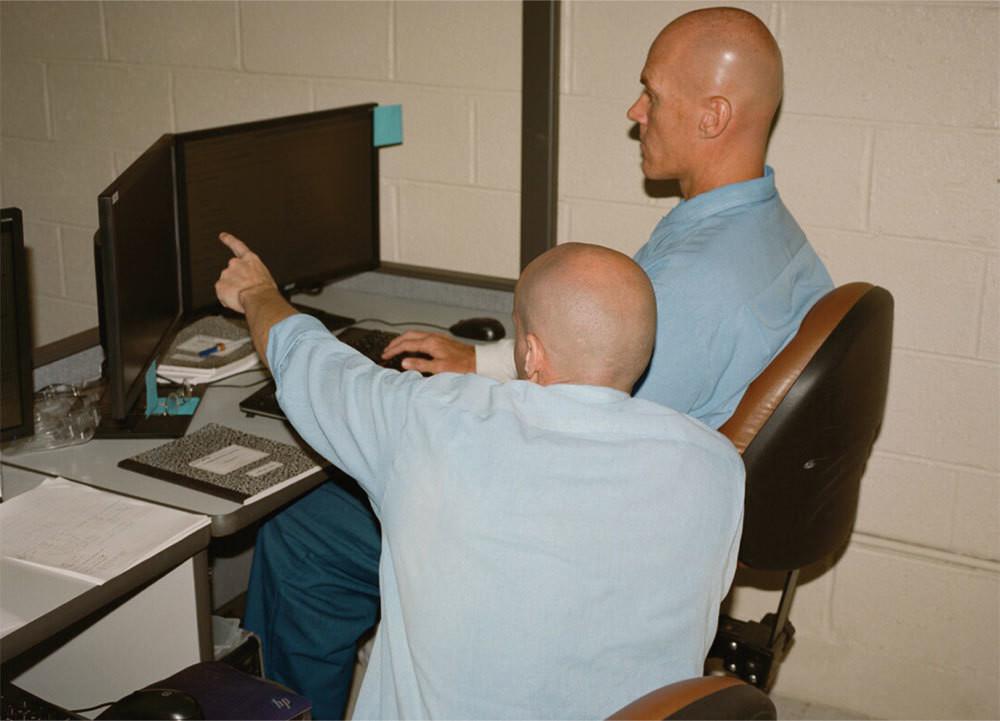

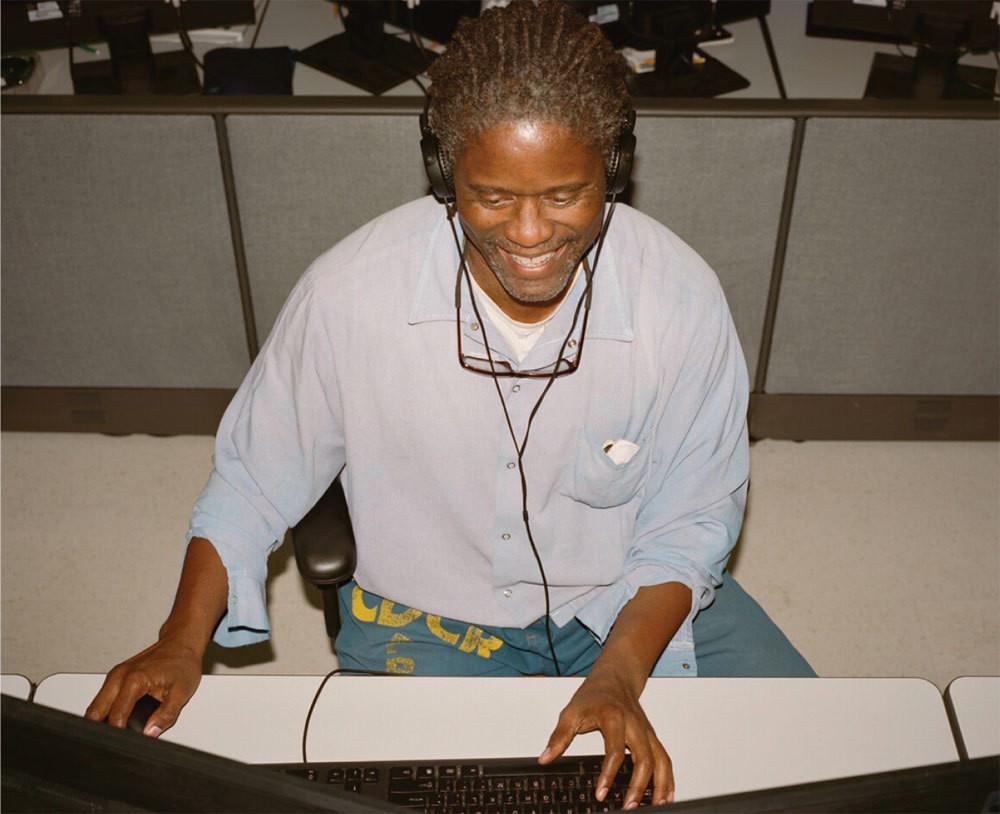

Code.7370 at San Quentin State Prison, in California, is thought to be the first-ever coding program for inmates in the country. Photos by Kent Andreasen

This article appears in VICE Magazine’s October Prison Issue

On a recent Wednesday morning at California’s San Quentin State Prison, 23 inmates sat before refurbished computers disconnected from the internet building websites and mobile apps. They worked not far from the more than 700 men being held on death row, just west of the old brick “dungeon” and gas chamber, and in the same facility where Johnny Cash played in 1969. Jonathan Gripshover, a bearded instructor who stood out against the sea of denim, circulated through the halogen-lit room. Organizers claim that the class he was leading, which is called Code.7370 and is a project of the nonprofit the Last Mile, is the first-ever in-prison coding program in the country. In January, the inmates will become part of Silicon Valley’s latest experimental employment arrangement when the Last Mile launches a program that will have them doing actual entry-level front-end coding work for companies on the outside. Through the arrangement, prisoners will earn $15 to 20 an hour, wages organizers say are comparable with those given to interns performing similar work. The program promises to be a modern-day foray beyond traditional prison jobs and a rare bridge between the technorati of the Bay Area and those living behind bars just next door.

Videos by VICE

Inmates at San Quentin have long worked for outside companies as part of the California Prison Industry Authority’s (CALPIA) joint-venture program, which promises “industry-comparable wages.” Other California inmates aren’t so lucky. Those working the nearly 6,400 CALPIA jobs, doing things like prison maintenance and vocational trades, make pennies on the dollar. Wages for even the most specialized and experienced laborers working CALPIA jobs max out at 95 cents an hour. Across the country, there are an estimated 2,500 prison and jail industries that create about $2 billion in revenue annually. Prison laborers have manufactured artisanal cheese for Whole Foods, sewn lingerie for Victoria’s Secret, and manned call centers for AT&T. For joint-venture programs like the one being developed through Code.7370, employers determine compensation in consultation with state officials. The aim of the work program, organizers say, is to give inmates both skills and savings they’ll be able to access once they’re released.

“Prison labor has a long and sordid history,” said Amy E. Lerman, a professor of public policy and political science at the University of California at Berkeley. “Seeing this program within this bigger context is important. There are two very different ways of seeing it. One is as part of a long history of what has basically been using cheap labor originally for agriculture work in the South. There are still prisons in the South that use chain-gang labor, and in recent years people have called it out as looking uncomfortably like plantation work. Now you have new, public-private-partnership cases where prisons are employing people to do trained customer-service work. It’s incredibly important for inmates to have something to do all day, and vocational training, particularly high-skilled labor, can hopefully give them skills they can use on the outside.”

To prepare to take on that work, the inmates in Code.7370 were finishing up on coding and design projects ahead of an assessment of their skills the following day. “At first I thought it was crazy,” said Chris Schuhmacher, an inmate in the class who has been incarcerated since 2001. “I always feel like the world of tech is passing me by. Everything is moving so fast. Like I’m the Flintstones and everyone else is the Jetsons.” He has never owned a smartphone or used anything beyond dial-up internet before, but in the course he has created an app called Fitness Monkey, which allows users to track their workouts and sobriety, offering rewards for steady progress.

Code.7370 meets eight hours a day, four days a week for six months, akin to the intensive boot-camp programs that have become popular in Silicon Valley. More than 200 inmates applied for the program at San Quentin, and the 23 who were admitted had to complete a written application, an in-person interview, and a technical assessment. The curriculum covers Java Script, HTML, CSS, and Python, and at the end of the course, inmates receive a certificate of graduation. The joint-venture work program launching in January already has a significant waiting list, organizers said.

In January, San Quentin will launch a work program through which inmates will do front-end coding for companies on the outside.

From the front, San Quentin could be mistaken for a castle or the mansion of an eccentric billionaire. It’s perched on the edge of San Francisco Bay, surrounded by palm trees; from the prison yard, multimillion-dollar homes nestled in the nearby hills are visible. San Quentin is California’s oldest prison and among its largest, with more than 4,000 inmates. The prison is so big it has its own zip code. Some guards joke that it was California’s “first gated community.”

The Bay Area is something of a Swiss-cheese society, with pockets of deep poverty amid vast swaths of wealth. It costs California almost $64,000 a year to incarcerate a single person, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and 55 percent of inmates who are released will be back within three years. Code.7370 was devised in response to that persistent recidivism rate.

The program arose about five years ago when Chris Redlitz, managing partner of venture-capital firm Transmedia Capital, visited San Quentin. He and other organizers from the Last Mile were concerned about the growing disconnect between the tech community in Silicon Valley and the ballooning population of men—disproportionally black and Latino—who were behind bars just an earshot away. In 2010, Redlitz began building an entrepreneurship program for prisoners. “I thought, There’s so much talent inside,” he said. Two years later, that curriculum graduated its first class, and in October 2014 it was expanded to create the coding-based program. The first class began in April of this year.

“So many people in San Francisco use offshore coders,” Redlitz said. “Are they doing background checks on those guys? No. It doesn’t matter. They care about the code, just when it comes back that it’s good. It should be the same here. Guys can do the work and do it well.” Redlitz described the inmates as ideal employees because they are so focused and driven. “It’s a tremendous opportunity,” he said.

“I go back to my bunk every night and just read about coding,” said Aly Tamboura, an inmate nearing the completion of a 14-year sentence. One of Tamboura’s coding projects has been to create interactive graphics with incarceration statistics. He toggled between elegant graphs with a sharp green line showing the ballooning prison population from 1960 to present, his eyes widening behind thick black glasses. He pointed to a bar graph with San Quentin’s population by race, the largest bar showing that 45.85 percent of inmates are black, like him. (A CDCR spokesperson said that the department could not reveal the racial makeup of the inmate population at San Quentin “for safety and security reasons.”) He pointed out patterns in the data, that rape and murder convictions were far less common in San Quentin than larceny and burglary charges. “Some of these things shocked me,” he said.

Former inmate Tulio Cardozo landed in prison on a conviction related to the explosion of his hash lab, which left his body covered in burns. Silicon Valley employers have been sympathetic, he said. “They think, Maybe you’ve been caught and some of the people sitting in this room didn’t get caught.”

When the Last Mile decided to bring the program into San Quentin, they faced a number of hurdles. Adapting a coding curriculum to be taught on dry-erase boards and without the internet was a challenge, said Wes Bailey, the Last Mile’s director of program operations. Bailey uploads the content for the lessons on a disk drive. “It’s remarkably hard to scrape that course,” he said of moving it from the web to a simulator that could be used in the prison.

All equipment has to be approved by prison officials, and the computers have to be inspected to ensure they don’t hook up to an external network. When students get stuck on a problem, they have no access to anything beyond textbooks. “I’m the local Google,” Gripshover, the onsite instructor, said. Many of the students read print copies of Wired, Fast Company, Entrepreneur, and Inc. or hear about various tech phenomena through television. They come with questions. “They say, ‘Show me Facebook,’” Gripshover said. “Show me Twitter. What’s Instagram? That’s how Tinder works? No way.” Additionally, inmates read Guy Kawasaki’s Enchantment, a Silicon Valley staple, and are taught skills like how to shake hands and make eye contact, social tools that will help them land a job in the industry. “Stuff you take for granted,” Gripshover said.

Organizers also hope to eventually create a private enterprise devoted to coding that could employ Code.7370 graduates when they finish their sentences in San Quentin. That would include people like Tulio Cardozo, who graduated from the Last Mile’s entrepreneurship program for recently released inmates in 2011. Since then, Cardozo has worked on a variety of web-development projects in the Bay Area. Roughly half of his body is covered in third-degree burns from when his hash lab exploded, an incident that also landed him in prison for five years. He said he has been pleasantly surprised by how empathetic employers have been to his past.

“I think it’s very similar to people who run companies,” Cardozo said. “Sometimes they just thrash them into the ground completely or by accident, either because it’s a bad idea or bad timing or bad execution. But a lot of those mistakes enable them to have the understanding to do it better the next time. They think, Maybe you’ve been caught and some of the people sitting in this room didn’t get caught. But this is now what you want to do and you have a reason for working harder than someone else.”

Read over on VICE News: Hard Labor: Here’s the Weird Shit Inmates Can Do for Work in US Prisons

Some prisons, including San Quentin, offer training in some manual skills, such as furniture repair. But with coding’s higher entry-level salaries, the temptation to return to a lucrative but potentially illegal business on the street may be lower. “I discounted myself,” Cardozo said. “If you can come out and make actual market wages, that makes a difference. There’s a shot at never going back. Because you can pay your bills, get food, put into a retirement plan, even buy a few toys, and feel good about what you’re doing. That’s forward thinking. If you’re not making enough or don’t have a skill that you can see as a career ten years from now, I don’t know how you’d be able to resist something else.” Whether or not Cardozo and inmates in Code.7370 will land jobs earning those wages remains to be seen. Since graduating, Cardozo has signed up for one of Silicon Valley’s hacker boot camps, hoping to build on the skills he learned from the Last Mile.

Meanwhile in San Quentin, the inmates were glued to screens. Jorge Heredia was among them. He has been incarcerated since 1998 and is serving a life sentence. In June, a parole board declined his request for release. On his screen, he showed me the green-and-black code that was the underbelly of Funky Onion, a website he made to connect imperfect-looking, but still edible, produce with consumers. At the top of the site was the venture’s tagline: “Even produce deserves a second chance.”

More

From VICE

-

Sanja Baljkas/Getty Images -

Terrance Barksdale from Pexels -

Christina House / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images -

Photo: Whiteland Police Department