Every photographer who’s made a career out of pressing shutter buttons in front of beautiful women owes a great debt to Harri Peccinotti. He was the first person to consistently capture the sexuality of everyday activities on camera: subversively pleasing sights like girls carefully sucking on popsicles, close-ups of butts on bike seats, and California beach bunnies unknowingly shot with telephoto lenses.

Harri was born in London in 1935. At 14, he dropped out of school to design album covers for the jazz label Esquire Records. In the 50s, he began working as an advertising photographer and eventually served as art director for glossy behemoths like Rolling Stone, Vogue, and Vanity Fair UK. But he will forever be remembered as the main brain behind Nova, a British magazine first published in 1965 that set new standards for both graphic and journalistic content by integrating ideas borrowed from the psychedelic subculture and underground press of the day.

In ’68, after completing an assignment in Vietnam, he photographed the now legendary Pirelli pinup calendar that paired love poems with photographic interpretations of the verses—alluring, tastefully shot women lounging around the Tunisian island of Djerba. Pirelli—and everyone in the world who wasn’t blind—liked it so much they invited him back the following year. This time Harri proceeded to up the raunch factor by featuring the aforementioned California girls in various states of undress.

Harri’s recent endeavors have focused on ethnographic reportage, filmmaking, and publishing books of his work. He also continues to shoot fashion and advertisements and is a photography consultant for the weekly French newsmagazine Le Nouvel Observateur. We met up with him in Paris in an attempt to wrest a few nuggets of wisdom out of one of the most talented men to ever hold a camera.

Vice: Bonjour, Harri. How did you become one of the greatest erotic photographers of all time?

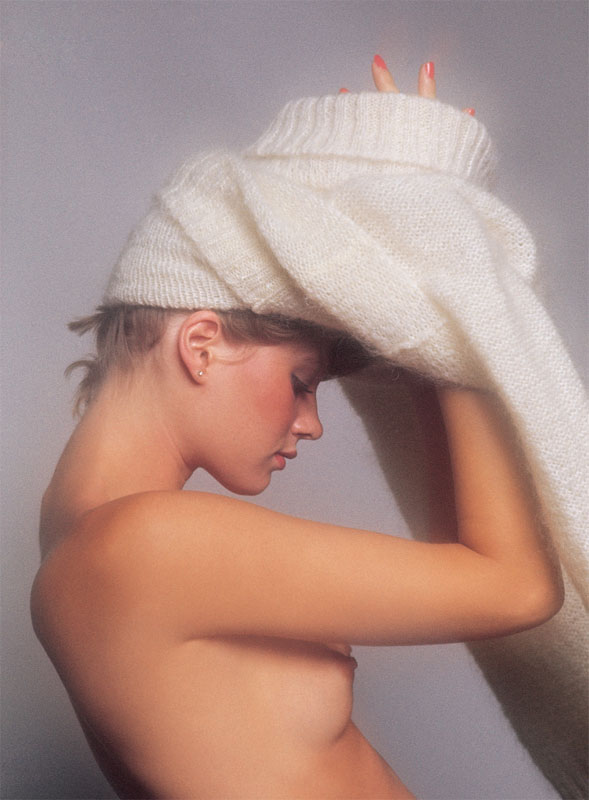

Harri Peccinotti: Honestly, I have no idea. I think it just happened by accident—by taking pictures of models with no clothes on. That’s how I did the ’68 Pirelli calendar. I don’t think there were any nipples shown in those calendars until the one I did, and even then there was only one nipple in it. Now there are crotches and God knows what everywhere. I’ve always been doing lots of close-ups, because I think it’s graphic, it’s getting closer. I suppose it becomes graphic when I’m doing it, and it’s the graphic side of the pictures that makes it erotic, not the other way around.

Lots of people cite Nova as one of the most influential magazines in history. Was there a particular impetus that inspired it?

It started as a sort of test for a particular market, which is why I had such great freedom. It was to see if there was a place for a magazine that treated women as intellectuals. I think it began with an awful subtitle, something like Nova: For the New Kind of Woman. Women’s liberation was going quite strong at the time.

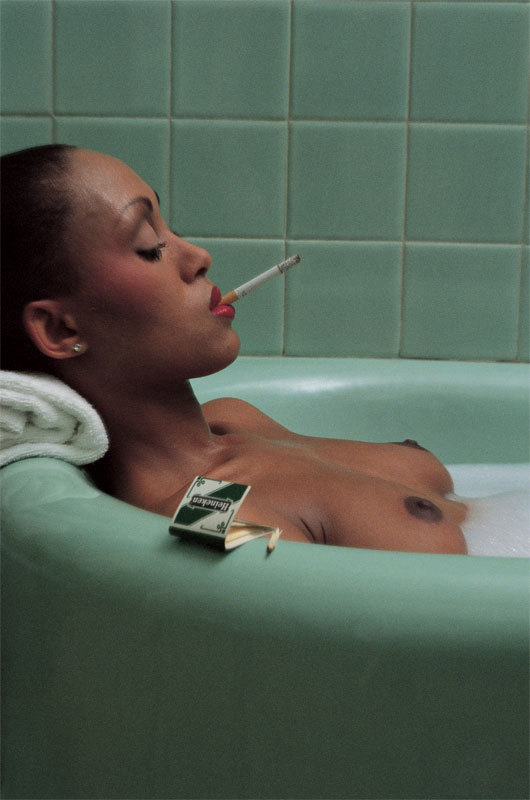

It seems perverse to run naked photos of women in a women’s magazine, especially at that time.

Well, all of the women working at the magazine—lots of great writers, such as Germaine Greer—were feminists, but they were not antisexual. It’s not like they did not use their sex, obviously. They were pretty open. For instance, there was an American hippie sort of guy who photographed his wife giving birth. He made this explicit series from the beginning to the end, so I bought them, and the editor agreed to publish them. The magazine sold out in about ten minutes because people weren’t used to that sort of thing—especially men.

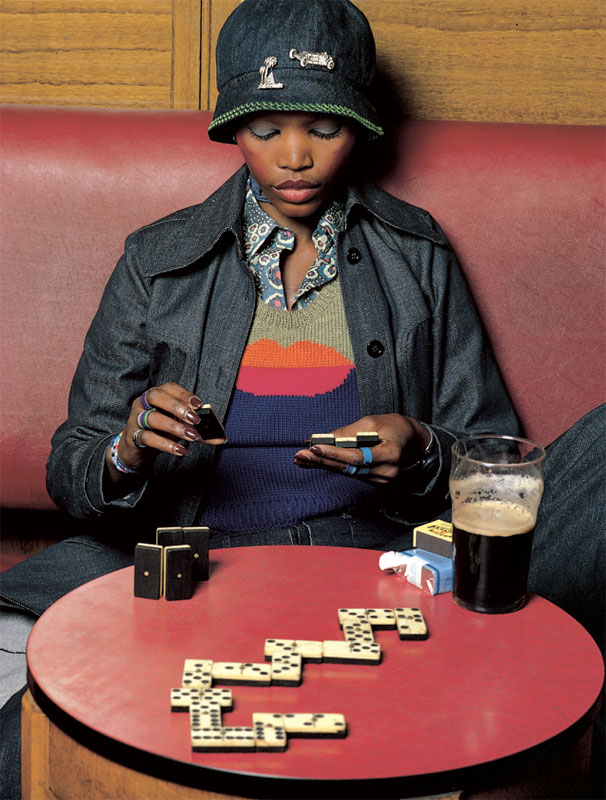

You were also one of the first to photograph and publish pictures of black models.

Yeah, I suppose. It happened quite naturally. I think all women are attractive. I couldn’t understand why there were no black models at the time.

Your subjects never seemed to be “perfect” like the supermodels of today.

No, I prefer it when they’re not. I think they are perfect, but not to some imaginary standard of size or shape. Like I said, all women are pretty attractive to me. The picture of the Japanese girl you chose was made for a makeup shoot in Japan. It was very hard to find real Japanese models in Japan; at the time, models in Japan were half-Korean or half-white, so she was not a model. She was an assistant of [Japanese fashion designer] Issey Miyake.

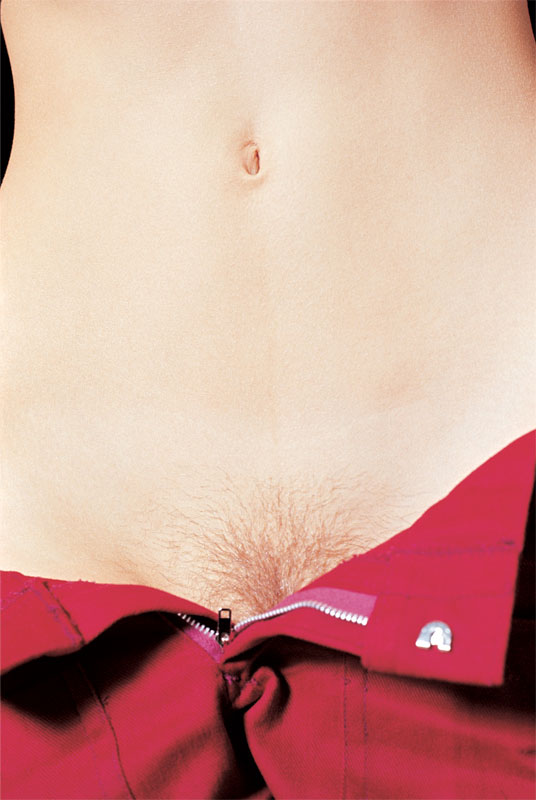

There was once an article in Nova that said something like “Let your hair grow!” Do you wish more women would abstain from shaving their armpits and nether regions?

Yeah, sure, I was fond of underarm hair and bushes. I quite like the idea of being hairy. I used to like these sort of earthy Italian and Spanish ladies who didn’t shave. It’s hard for me to photograph girls now because they all have pubic hair shaved into a heart shape and belly-button rings and tattoos.

Before we finish, I want to see if you’re willing to divulge your greatest secret: How did you make your models so comfortable? It seems like they would’ve done anything for you as long as you were holding a camera.

I don’t know. I’m not pushy. I’m just quiet. At that time I was roughly the same age as the models—at least sort of sexually connected to that age, so there were some things going on. Now I’m more like their grandfather’s age, but it still feels great.

Harri Peccinotti’s new book, H.P., collects over 40 years of his best work and is out now from Damiani.

Videos by VICE

More

From VICE

-

Kelly Sullivan/Getty Images -

-

(Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Spotify) -

WWE via Getty Images