Fighting Words is a column in which writers rub you the wrong way with their unpopular but well-argued opinions on fitness, health, nutrition, what have you. Got something to get off your chest? Send your pitch to tonic@vice.com.

As a diagnosis, “attention deficit” is a misnomer. People with ADHD do not pay less attention. In fact, we pay more—so much more it’s often too much. Our impulse is to take in extra stimuli instead of screening it out. We hear and observe everything, which makes focusing difficult.

When your brain’s made to let everything in, the upside is an ability to make connections no one else can. Since we take in more info than people without ADHD, we can connect the data they overlook. That’s the secret to Jim Carrey’s off-the-wall humor, Richard Branson’s ability to see into an industry’s future, and the way quarterback Terry Bradshaw always knew where the ball was.

Videos by VICE

You’d think the neurological secret to thinking like Richard Branson would be something to brag about at work. Ask HR experts, though, and they recommend you keep your mouth shut. Laura MacLeod, a licensed clinical social worker and HR consultant, says, “Divulging [your] ADHD diagnosis burdens others with personal information. It’s boundary-crossing that’s not appropriate in the workplace.”

As someone with ADHD, I find this pretty insulting. I once had a client say he wanted to bend me over and ride me like a donkey. That was boundary-crossing and inappropriate for the workplace. But telling people about your brain, and how it thinks as fast as The Six Million Dollar Man moves? That’s not.

So I asked MacLeod if she was at all familiar with ADHD or even knew what it was. She said she did, but my question gave her the all-too-important opportunity to clarify: “Most people don’t.” That sent me on a trip down memory lane to every workplace divulgence gone wrong. In each instance, the person I told about my ADHD initially thought there was something wrong with me. “For every story of self-disclosure that has a happy ending,” Elaine Taylor-Klaus says, “there is one where the disclosure results in more trouble in the workplace.”

Taylor-Klaus is cofounder of ImpactADHD, a coaching consultancy. When asked her opinion on whether to tell coworkers that you have it, she calls the question “a tough one” and says, “It really does depend.”

In the instances where she’s counseled a client to divulge, it was because something environmental made it impossible for that client to effectively work without change, like the stimuli overload of open-office seating. Her example is why, when I was an employer, I would have wanted someone with ADHD to tell me. I’ve owned two businesses and know firsthand that no employee is perfect. But there is a marked difference between an employee who underperforms because of something she can’t help—like ADHD—and one who simply doesn’t desire to improve.

When you’re managing ADHDers, the difference can be hard to see. Turns out the downside of a super-charged brain is an inability to perform microtasks that people without Attention Deficit label as “easy.” To quote David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue and an ADHDer, “I have an easier time planning a 20-aircraft fleet than I do paying the light bill.” This translates to supervisors who aren’t in the know seeing us “slacking” on the “easy” things and thinking that poor performance stems from not wanting to do to the work.

This focus on improving employee productivity is the basis for psychologist Maelisa Hall’s advice to clients. While she doesn’t contend that you “tell [your] boss about [your] diagnosis right away,” she does recommend that you talk to them about your symptoms. “It’s best to first focus on needs and what makes [you] productive. For example, instead of saying, ‘I have ADHD so I need to go sit in the conference room to focus and complete this project’ it is just as helpful to say to a boss, ‘I really need to reduce my distractions so that I can focus on completing this project. I’m going to spend the next two hours in the conference room rather than in my noisy cubicle.’”

As a former employer, I agree with her. This also connects, to a kinder degree, with MacLeod’s point. Supervisors aren’t shrinks, and you can’t expect them to understand every diagnosis on the planet. But if there’s one thing bosses do understand, or good ones at least, it’s efficiency. They don’t necessarily need to know you have ADHD, they just need to know what needs to happen for you to be better at your job.

Focusing on your needs and the company’s needs also keeps HR out of it. When asked whether she thinks employees should share their ADHD diagnosis, Laurie Brednich, CEO of HR resource site HR Company Store, jumps right into explaining the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) and all the accommodations it says you legally might or might not have the right to require. “Employers are required to have an interactive conversation to determine the employee’s need and if their request is reasonably accommodated,” she says, recommending people talk to “both their supervisor and HR simultaneously.”

Compared to Hall’s suggestion to simply ask, “Can I just sit in the conference room?” filing for ADA accommodations and bringing in HR sounds like a quick way to make yourself a pain in the ass. Or, as Brednich more politely puts it, the result might be “conscious or unconscious bias with your coworkers and superiors.”

In other words: Stigma. That’s the word MacLeod uses when she recommends we all keep our mouths shut. There are people who understand it and people who don’t. And because that second group doesn’t immediately get how amazing our minds are—and since ADHD’s misnomer of a name has the word “disorder” in it, they’re much more likely to think our difference signals something wrong with us. Discrimination is, of course, totally illegal, but it’s also often hard to prove.

As an employer, I have to agree with Hall: People with ADHD can solve most workplace difficulties by explaining the symptom then working with their workplace toward solution. You don’t have to tell anyone you have it.

Read This Next: What Really Happens When You Drink While On Psych Meds?

More

From VICE

-

Bill Murray and Eddie Murphy in conversation about…something (Photo by Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images) -

Zootopia 2 -

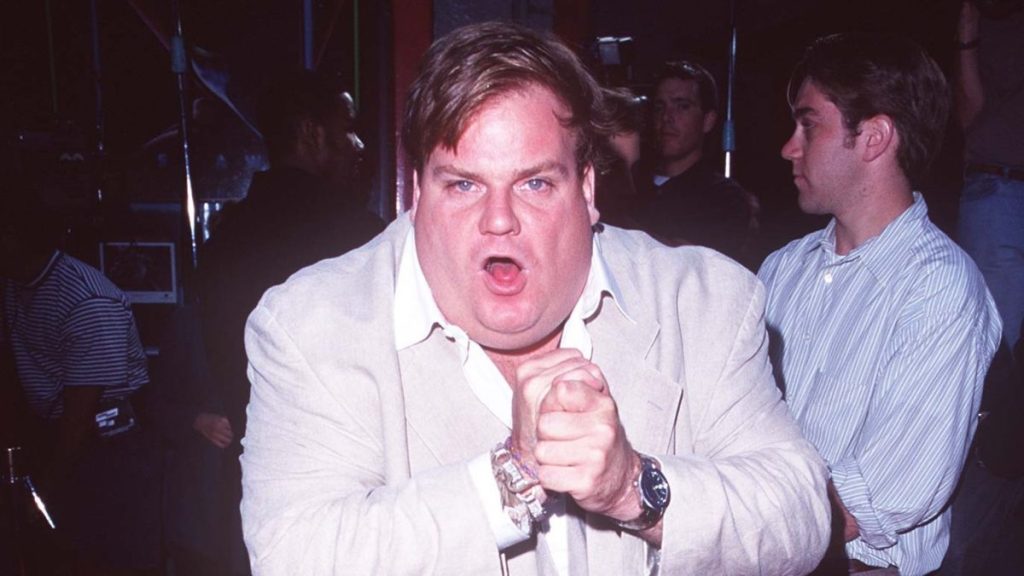

Chris Farley (Photo by SGranitz/WireImage) -

John Belushi (Photo by Michael Gold/Getty Images)