Don realized he was being kidnapped about 10 minutes after he stepped into the beat-up green SUV on a street in Tijuana. He was trying to get back to his wife and two daughters in San Jose, California, where he’d lived for more than a decade before being deported back to Mexico.

With no legal way to reunite with his family, Don had agreed to pay the smugglers $12,000 to sneak him across the border and up to Los Angeles. But as the two men drove him through Tijuana, he overheard them talking and realized they had other plans.

Videos by VICE

“Did you bring the gun?”

“Yeah, in case they want to run.”

They passed a Mexican police patrol, but Don didn’t bother to scream—he assumed the cops were friendly with his captors, or perhaps even in on the kidnapping. As the SUV pulled up to a house, the men forced a hood over his head and tied up his feet and arms. He thought to himself, “This is it; I am never going to see my family again.”

In California, Don’s wife got a phone call. A man whose voice she didn’t recognize demanded she pay $10,000 through wire transfers for her husband’s release. She insisted on talking to Don. The kidnappers held the phone to his mouth.

“Get the money, please, get it,” he told her. “Ask my brothers. Find someone who will loan it to you. Help me.”

Don was kidnapped on January 13, 2014. In the years since, tens of thousands of other migrants have endured similar nightmares. The United States has spent billions on fencing, drones, and the physical security of the border, but it’s done relatively little to disrupt the way criminal organizations profit from human smuggling and kidnapping. At the heart of it are wire transfers through American companies, which are still by far the most common way for kidnappers to extort ransom payments and for coyotes to collect fees.

VICE World News reviewed 40 ransom payments made through money transfers in eight different kidnapping cases from 2014 through January of this year. Virtually all of the money flowed through U.S. companies, mostly through Western Union and MoneyGram but also Walmart and lesser-known companies like Ria. By our rough estimate, criminal organizations in Mexico have made around $800 million on migrant kidnappings alone over the past decade, and money-transfer companies received a cut on nearly every transaction through fees and exchange rates. American corporations are profiting from kidnappings.

Ransom payments are a drop in the bucket compared to the fees people willingly fork over to be smuggled into the U.S. American companies profit from these deals too, through relatives wiring money to the coyotes. The cost of crossing illegally ranges from $150 to $15,000, depending on the stretch of the border, the destination in the U.S, and where the journey began. The total paid to smugglers, mostly through wire transfers, is in the range of $2 billion annually, according to law enforcement and think tank estimates.

To understand this illicit economy, VICE World News interviewed people on all sides of the clandestine business, including human smugglers, current and former investigators for U.S. federal law enforcement agencies, and anti–money laundering experts who tell companies how to avoid breaking the law. They described a system where companies have a profit incentive to turn a blind eye to extortion and smuggling payments; where “suspicious activity reports” go ignored because law enforcement rarely investigates; and where politicians decry inhumanity at the border but overlook the pivotal role played by U.S. companies.

“Right now no one is being told human smuggling is a priority—period.”

“Until financial institutions are told they need to be actively monitoring their transactions for kidnapping ransom payments, they are not going to do it,” said Alison Jimenez, president of Dynamic Securities Analytics, a U.S.-based anti–money laundering company. “The priorities are what the government tells them are the priorities, and right now no one is being told human smuggling is a priority—period.”

In two of the eight kidnapping cases we analyzed, victims sought help from U.S. authorities. After Don was kidnapped in Tijuana, the FBI even got involved. Nothing came of it. Don and his wife requested anonymity out of fear the kidnappers would track them down, even in the U.S.

But it doesn’t take much to investigate the kidnapping rings: The paper trail is robust. Money transfers include not only a tracking number but also the names of the people receiving the money, where it was collected, and at exactly what time.

Don’s wife kept all of the numbers the kidnappers called from and the names of the people she wired money to. We tracked one of them down.

Anatomy of a Ransom Payment

The kidnapper gave detailed instructions to Don’s wife, Maria. If she wanted to see her husband alive, she had to make four deposits of $2,500 each to four people in Tijuana.

Maria scraped together all she and Don had, then turned to relatives for the rest. She drove to Tropicana Foods in San Jose, a market that sells everything from groceries to jewelry and clothes. At the checkout counter, customers can also send cash abroad using a number of money transfer companies. Maria chose Ria, a California-based company with nearly half a million locations in 159 countries, because it offered the best exchange rate.

Maria’s in-laws each deposited $2,500. Ria charged $25 per transfer. The payments were “structured” or broken up into smaller amounts in an effort to avoid triggering laws that require companies like Ria to keep detailed records of any transaction over $3,000 and monitor for suspicious behavior.

Even so, when Maria tried to send her portion, Ria’s system blocked it. Undeterred, she simply went to another Ria outlet a few miles away. This time, the transfer went through. For the $10,000 ransom payment, Ria earned $100 in fees. Ria and other companies also profit from changing dollars into pesos by charging steep exchange rates.

Financial services companies play a pivotal role helping immigrants in the U.S. support loved ones back home through remittances. But the very business model of moving money instantly with few questions asked is also ideal for criminals. So companies spend millions of dollars on anti–money laundering training and digital safeguards like automatic red-flag alerts.

It’s hard to distinguish remittances from suspicious transactions, but not impossible, anti–money laundering experts and executives at money transfer companies told us. Telltale signs include the dollar amount and unusual patterns of how and where the money is sent. There are also limits on the volume and quantity of money that can be sent between locations, and the biggest companies have sophisticated tracking systems that allow them to geographically pinpoint where the money is flowing in both real time and historically. This alerts them to suspicious transactions made in smaller dollar amounts, like a series of ransom payments.

Do you work at a money transfer company? Know something about kidnapping or human smuggling? We’d like to hear from you. Contact: keegan.hamilton@vice.com and/or emily.green@vice.com.

Such measures have evolved over the years, largely in response to slaps on the wrist from law enforcement. In 2010, Western Union agreed to pay $94 million to settle a lawsuit with the Arizona attorney general’s office, acknowledging that its employees “were knowingly engaged in a pattern of money laundering violations that facilitated human smuggling from Mexico into the United States.”

Terry Goddard, the former Arizona attorney general who oversaw the 2010 litigation, said smuggling networks adapted within a matter of days to circumvent more robust transaction monitoring. When the threshold dropped to $500, Goddard said, $499 payments soon followed. Goddard, now in private practice, said federal law enforcement was reluctant to get involved.

“It just did not rise to their level of importance,” Goddard said. “When you don’t have people saying, ‘This is a priority, this is what we need to spend our resources on,’ it’s going to fall through the crack. And I’m afraid that’s what’s happening now.”

“The cartel has its rules. Those who don’t pay are disappeared.”

Scott Apodaca, Western Union’s global head of financial intelligence, said the company now has an entire unit with over 500 employees who “develop rules and specific algorithms and financial footprints that are specifically designed for human smuggling or even human trafficking.”

“We can’t catch every single bad transaction,” Apodaca told VICE World News. “We realize that there are times, that there are isolated incidents, that transactions may go undetected and that it’s not 100 percent guaranteed that every transaction that is reviewed and monitored related to illicit activity will ultimately be stopped.”

Most family members of kidnap victims pay $2,000-$4,000 to free the loved one, according to receipts we reviewed and interviews with nearly a dozen victims. With few exceptions, the kidnappings are carried out by cartels or affiliated criminal groups. Like Maria, the victims usually enlist friends and relatives to help send the money to avoid being blocked. The initial extortion is often just the beginning. If kidnappers sense victims aren’t bled dry, they demand more money. Such was the case with Maria and Don.

Hours after Maria sent the payments, the kidnappers called back and angrily reported that one of the $2,500 transactions was blocked on their end. Maria was able to retrieve that money, but the man told her she needed to come up with another $8,000 to make up for the loss or she’d never see Don again.

Don’s mother had recently sold a house and split the money among her children. Those funds would now be used to pay off the kidnappers.

The kidnappers gave Maria a new list of four names and again instructed her to send the money in parts. She returned to Tropicana Foods and attempted to make the transfer, but this time the teller said the amount was too large. The system worked as intended, but not in Maria’s favor. She wanted the money to go through. Don’s life depended on it.

A spokesperson for Ria’s parent company, Euronet Worldwide, declined to provide further information about Maria and Don’s case but said the company was “pleased that our systems and processes were successful in identifying and blocking the extortion payments.”

“We can say, unequivocally and emphatically, that Ria has been an industry thought leader and a big contributor to combating any illicit activities that could try to permeate our service,” said Stephanie Taylor, Euronet’s director of financial planning and investor relations.

But John Cassara, a former U.S. Treasury Department special agent, said stopping the money in this case might have been a mistake. While he cautioned that he didn’t know all the details of Don’s kidnapping, watching the payments happen can be very helpful to investigators.

“The transfers shouldn’t automatically be shut down,” Cassara said. “If law enforcement knew about it and had the resources, they would say this is a perfect opportunity for us to monitor this live.”

Instead, Maria’s money was frozen, and she was terrified of going to the police. The kidnappers were furious when Maria called to explain the situation. They accused her of lying and told her this time she would have to hand over the money in person, in Los Angeles.

Two Bottles of Tequila

In Tijuana, Don’s nightmare was just beginning.

He recalled being held alone, blindfolded and bound. He received only water, no food. The first guard kicked him, he said, and another took down Don’s pants and touched his genitals.

“He would touch my parts and tell me that he was going to help me, that I needed to do what he said, because if I didn’t, they were going to kill me,” Don said. “I was practically like an animal,” he added, wiping tears from his face. “It was like they were going to sacrifice me.”

Don, 48, is slim and soft-spoken. He had lived on and off for two decades in California, working in construction and raising his two daughters with Maria. He had been deported previously trying to enter the U.S., and his 2013 removal came after a traffic stop led to police finding a weapon—a collector’s item Japanese throwing star, or shuriken.

On the third day of his kidnapping, the man who liked to touch Don came into the room and announced: “Te vas a tomar dos Tonayans.” He carried two bottles of Tonayan, a bottom-shelf brand of tequila that comes in a plastic jug. Don would be released, but first he had to drink.

With no other choice, Don began to down the tequila. He blacked out and woke up next to a highway. He was beaten and bloodied, his clothes dirty and stained. He begged for help, but passers-by kept their distance.

Don managed to get to a church in Tijuana. A man outside agreed to call Don’s home, and Maria picked up. Over the previous three days, she had paid the kidnappers $14,500 for Don’s release: $7,500 in money transfers, plus the additional $7,000 in cash, which her in-laws fearfully handed off at a park in East Los Angeles.

Maria arranged for a cousin to pick up Don. Despite everything he had endured, Don resolved to reunite with his family. They found yet another coyote to smuggle him across near Calexico, California.

Don’s relentless determination to cross the border is shared by millions of other people. In March alone, U.S. border agents reported 171,000 apprehensions, including 18,800 unaccompanied children. The vast majority paid a smuggler at some point in their journey. Most of that money traveled through U.S. financial institutions. Migrants rarely carry cash because it’s too dangerous, and wire transfers offer a degree of protection against theft.

In recent months, smugglers have capitalized on the perception that President Joe Biden is embracing a more humanitarian approach than his predecessor to immigrants and asylum seekers, spreading the word on Facebook and WhatsApp that children are being allowed in. But nearly all others are still being turned away, which fuels illegal crossing attempts and leaves people especially vulnerable to kidnappings.

There are no reliable statistics on migrant kidnappings. The Mexican government’s most recent report, from 2011, documented more than 11,000 in just six months. If that pace continued, it would work out to over 200,000 kidnappings in a decade. Assuming the kidnappers received around $2,000-$4,000 per victim, the going rate in the receipts we reviewed, that works out to $40 million–$80 million annually paid out in ransoms. The true total is impossible to pin down, since most kidnappings go unreported and only the most horrifying cases ever make headlines.

“I was practically like an animal. It was like they were going to sacrifice me.”

The most recent viral case involved footage of a tearful 10-year-old Nicaraguan boy found wandering alone in the Texas desert. The boy was reportedly kidnapped in Mexico along with his mother and held for a $10,000 ransom. Relatives in Florida could only come up with half the money, which one family member told VICE World News they wired to the kidnappers via various money transfer companies and apps, including Western Union. They released the boy soon after, but they continued to hold his mom hostage.

In hopes of avoiding a similar fate, migrants pay smugglers upwards of $14,000 to ferry them from Guatemala or Honduras to a given city in the U.S., usually taking out loans at exorbitant interest rates and putting up their family’s land for collateral to pay the fee. The trip is marketed as all-inclusive, including not only food but also the fee paid to cartels to pass through territory they control.

The low-budget option is to make the trek north without a smuggler and just pay for the border crossing into the U.S., which runs from a couple hundred to a couple thousand dollars. Payment is non-negotiable.

“The cartel has its rules,” said one smuggler in Juarez who asked to go by the name Spider. “Those who don’t pay are disappeared.”

At 43, Spider has been in the smuggling business for 20 years. Back when he was 13, he could cross freely into El Paso. Now he charges $1,500-$1,800 for the same trip. A third of the fee goes to the cartel that controls his portion of the Rio Grande. To reach Dallas, the price goes up to $5,500. He said he’d crossed 12 people the day before. His preferred wire service is MoneyGram, but he also collects using Elektra, BanCoppel, and others.

MoneyGram said in a statement that it has “some of the most stringent and robust compliance controls in the industry” and “invested millions in developing a best-in-class, technology-enabled compliance program to protect consumers and ensure its services are utilized for their true purpose.” It added that “MoneyGram works closely with law enforcement agencies around the world.”

Elektra also said it has “one of the most robust money laundering prevention programs internationally.”

“We are one of the few institutions to have the technological capacity to group and limit an individual’s transactions in real time, using multiple parameters aimed at detecting crimes such as human trafficking,” the company said in a statement. It added that suspicious activities are shared with the appropriate authorities.

BanCoppel declined to comment.

Spider’s money is picked up by a rotating cast of family, friends, and acquaintances whom he has trained on what to say if questioned. If the teller asks who sent the money, for example, they should say a relative—but a distant one, like a stepfather or brother-in-law—or even a lover. His people can usually collect up to four payments with one company before they are frozen out, he said, but after a few months they’re back in business.

“It’s a sweet deal for everyone,” Spider said. “Even the people picking up the money make $25 for every deposit.”

If the U.S. ever enacts immigration reform and allows more legal crossings, he joked, “the coyotes will have to go on strike.”

The smuggling doesn’t end at the U.S. border. Once migrants cross the Rio Grande, they are typically handed off to another member of the organization, who drives them to a safe house where they wait for payment to be collected before they are freed or continue north.

Ramón, a smuggler in Arizona, is a U.S. citizen who makes around $1,200 per trip transporting up to six people at a time from the border to Phoenix or Tucson. He compared the service to a travel agency, with the coyotes as “agents” who refer clients, and him as the “chauffeur” driving the last leg of the journey.

“It’s a real ego stroke, to be honest,” Ramón said. “If you get them across, they’re like, ‘Thank you, thank you so much.’”

The line between smuggling and kidnapping can be blurry, with people held for days or weeks at stash houses until they pay what’s owed—and sometimes more. Ramón recalled witnessing a stash house worker threaten someone by firing gunshots into the air: “He was like, ‘You have to hurry, get all these account numbers otherwise I’m going to have to call this guy’s mom and tell her why her son is tied up.’”

Evidence of extortion payments connected to stash houses in the U.S. shows up in receipts we reviewed. One family in New Jersey used the money transfer service Walmart2Walmart to send two payments totaling $1,000 to free family members held in Texas.

A Walmart spokesperson said the company has “numerous front-end controls and back-end monitoring to prevent money laundering activity, including potential human trafficking,” and that employees are trained to report suspicious activity to law enforcement.

Ramón said he’s seen prepaid debit cards and electronic bank transfers used occasionally, but nothing more high-tech.

“The way they send transfers of money hasn’t changed in probably 30 years,” he said. “I have some buddies that can do some crazy things with bitcoin, but I’m not that cool. It’s old-school.”

“I Was Terrified”

Two months after Don’s kidnapping, Maria went to the police. Her experience was a case study in why such crimes are rarely ever reported, let alone investigated or successfully prosecuted.

She knew after delivering the second ransom payment that the criminals had connections in California, and she feared retaliation. She also knew of other people—family members of church friends—who’d been kidnapped while crossing the border.

“I was terrified,” she said. “But my friends at the church said to me, ‘You have to speak up so other people will also overcome their fear and denounce what’s happening. Because if people don’t say what happened, it remains a secret and nothing ever changes.’”

She drove to the San Jose Police Department, accompanied by a member of her church. She recounted in detail the kidnapping to a police officer, providing copies of the money transfer receipts and the kidnappers’ phone numbers. She found the officer dismissive and more focused on her immigration status. The police referred the case to federal law enforcement. A San Jose Police spokesperson said officers are “expected to treat all of our citizens with courtesy and respect.”

Two FBI agents arrived at Maria’s house a few weeks later. She retold the story, again providing copies of all the records. Maria said she never heard from them again.

A spokesperson for the FBI did not address the specifics of Don’s case but pointed to the 2015 arrest of a San Diego County man as proof the agency takes kidnappings seriously. In that instance, at least two dozen victims were abducted, beaten, and raped in Tijuana. One person responsible received 18 months in prison; four others in Mexico were not apprehended.

“In the U.S., financial institutions are cooperative and responsive to legal process requests for records,” the FBI said. “Money transfer services are often used by offenders who are quick to adapt to ever-changing regulations regarding money transfers.”

Using the same information Maria gave the San Jose Police Department, VICE World News called one of the kidnappers in Tijuana. The man who picked up skeptically asked what we wanted. When we asked to get his side of the story, he hung up the phone.

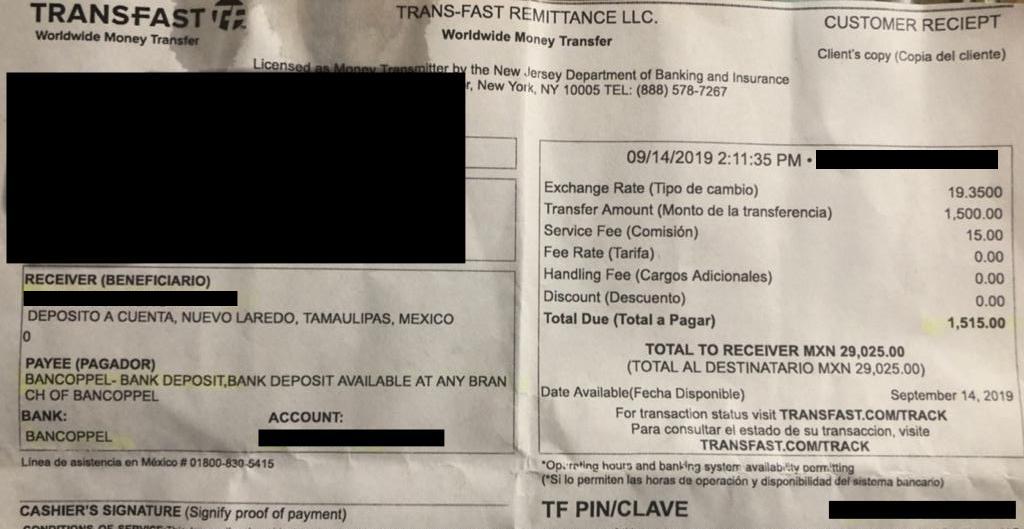

Other kidnapping victims also shared money transfer receipts. Using the recipient names, we located some of the individuals responsible for collecting the ransoms in a matter of minutes, just by searching on Facebook. One man who ignored our messages lives in the Mexican border city of Nuevo Laredo. He lists his occupation as “Boss of Los Zetas,” a notoriously violent cartel, though he looks to be 20 at most. He picked up a $1,500 money transfer from Mastercard subsidiary Transfast, one of four payments sent in the kidnapping of an Ecuadorian family trying to reach the U.S.

“We use a combination of the latest technologies and best practices to monitor and analyze patterns of potentially suspicious activity” and “actively report such activity to relevant law enforcement authorities so they can take the appropriate action,” Mastercard said in a statement, adding that it no longer provides money-exchange services to individual consumers.

The U.S. and Mexico used to work together to combat human smuggling under a joint operation between Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Mexico’s attorney general. From 2005 to 2016, CBP referred over 3,000 cases for prosecution in the Mexican justice system. But starting in 2017, according to CBP, Mexico began requiring victims to appear in court to testify against smugglers, who often have ties to organized crime. The program predictably fizzled. CBP referred a total of nine cases over the last four years, according to the agency.

Mexico’s attorney general didn’t respond to a request for comment about why it implemented this seemingly unrealistic requirement. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador promised to protect migrants as a candidate, but as president he has deployed the military to crack down on them and bowed to U.S. demands on immigration.

Money transfer companies and U.S. authorities have tools to track the millions of dollars being sent to human smugglers and kidnappers. But most of the information gets lost in a web of bureaucracy.

“Financial institutions along the spectrum, they’re making a killing.”

When companies spot something shady, such as a large transaction or structuring, they are obligated to file a “Suspicious Activity Report,” or SAR, with the U.S. Treasury Department. The system is an information black hole. Last year, companies filed 2.5 million SARs, so many that the database of reports is unwieldy almost to the point of uselessness, especially for kidnappings that involve relatively small dollar amounts.

“Their mandate was to be a filing cabinet, to be a data repository,” said Jimenez, the anti–money laundering expert. “Very few law enforcement use SARs as a starting point for an investigation. They use it as a supplement.”

The SARs offer a way for companies to shield themselves. The reports don’t automatically trigger alarm bells, and if investigators come back later, the company can point to proof they took the required action. The company gets to pocket the money and continue business as usual.

Even in a best-case scenario, it’s likely the kidnappers in Don’s case would have escaped justice. While the kidnappers had associates in Los Angeles, only Mexican authorities could arrest the abductors in Tijuana. There’s no way for U.S. agents to track the phones of the kidnappers and arrest them without involving Mexican law enforcement.

“The roadblocks in that are serious,” one federal agent said. “That would have to be something created that’s nonexistent right now.”

Debt and Trauma

As soon as Don crossed into Arizona with his second coyote, immigration agents began pursuing the group, and eventually detained them. The federal authorities wanted to prosecute the smuggler, and Don agreed to cooperate as a witness in the case.

He also told them about the kidnapping, and after a year in detention, a judge ordered him released, ruling he had a “credible fear” of returning to Mexico. He and Maria are currently pursuing U-visas for undocumented immigrants who are victims of crime and cooperate with law enforcement. Such visas could be used to help safely resettle other kidnapping victims, but the government issues only 10,000 per year, and the typical wait for one is currently 5-10 years. If Don’s visa application is denied, he could eventually face deportation to Mexico.

Don reunited with his family in San Jose on Dec.19, 2014, but he has not lived happily ever after. The day of his return was his youngest daughter’s birthday. But when he saw his daughters, he couldn’t embrace them.

“I felt weird, like I wasn’t myself,” he said. “My daughters could feel my rejection as they hugged me. It didn’t feel good to hug my daughters.”

To this day, he cannot hug his daughters like he did before the kidnapping. And while he has moments or days of feeling normal, the memories come flooding back. “It’s difficult to live like this,” he said, weeping.

Nothing ever came of the FBI investigation. In 2017, Don’s attorney contacted the FBI agent who visited Maria. The agent said in an email that the case was closed because Don could not be reached for an interview while he was in ICE custody.

These days, Maria works in a Mexican restaurant, and Don has returned to the construction industry, laying tile in bathrooms and kitchens for $28 an hour, but the pandemic has made jobs scarce. They still owe money to their relatives who helped pay the $14,500 ransom.

Money transfer companies have seen their fortunes rise in the years since Don’s kidnapping. Remittances to Latin America are a $100 billion-per-year industry.

“Financial institutions along the spectrum, they’re making a killing,” said Richard Lee Johnson, a doctoral researcher at the University of Arizona who studies the relationship between debt and migration in Guatemala. “It’s a whole economy. They’ll say, ‘This isn’t illicit,’ but they don’t necessarily investigate what’s going on. They’re happy to receive the money.”

Without changes that radically open pathways for immigrants to live and work in the U.S. legally, cash will keep flowing through money transfer companies and into the pockets of criminals. Faced with a wave of desperate people trying to reach the U.S., the Biden administration has adopted an old strategy: Pressuring Mexico and Central American countries to stop people from crossing their borders. The strategy effectively pushes people to take ever more dangerous journeys, making them more vulnerable to being kidnapped.

Don and Maria still hold out hope the kidnappers will be caught and prosecuted, but they know the reality of that happening gets dimmer with every passing day. “That money will never be returned to me,” Don said. “But if there were justice in my case, so other families didn’t go through the same, that would be enough.”

Luis Chaparro contributed reporting from Ciudad Juárez.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Francesco Castaldo/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images) -

M Scott Brauer/Bloomberg via Getty Images -

Firefly Aerospace/YouTube -

Justin Paget / Getty Images