Jakarta’s incumbent governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a man dogged by blasphemy allegations and protests through much of the election, lost the race to opposition candidate Anies Baswedan, according to early quick count results that have left some to question whether pluralism was losing ground in Indonesia.

“The problem is, the current opinions in the election were formed out of intolerance,” said Yohanes Sulaiman, a political analyst at Jenderal Achmad Yani University. “[And] in his campaign, Anies didn’t seem to be rooting for liberalism.”

Videos by VICE

Anies and his running mate Sandiaga Uno won 58 percent of the vote, according to unofficial quick counts conducted by Saiful Mujani Research & Consulting. Quick counts have historically been accurate enough to call an election in Indonesia.

Watch: VICE Asks: What was the most-important issue for you this election?

The two men held in a press conference shortly after 4 p.m. where they were congratulated for winning the election on live television by Prabowo Subianto, the chairman of opposition party Gerindra, the main backer of the Anies-Sandi ticket.

Anies, in a nod to the divisiveness of the election, said he was committed to preserving the capital’s ethnic and religious diversity and working to bury some of the uglier rhetoric that had marred the campaign season.

“We are committed to ensuring diversity in Jakarta,” Anies said in a televised press conference. “And we are committed to maintaining not only this diversity, but to also preserve the unity of Jakarta. We want to celebrate the diversity, celebrate the unity, and the cohesion.”

His running mate Sandi said the pair were looking forward to engaging with the incumbent governor, a man popularly known as Ahok, and that they were ready to put the past few months behind them.

“Insha Allah, we will communicate well,” Sandi said. “All we want to say is that we’re good friends, so let’s unite again. Let’s forget about the previous months and look ahead to five glorious years for Jakarta.”

Basuki Tjahaja Purnama. Reuters Photo

Ahok and his running mate incumbent deputy governor Djarot Saiful Hidayat conceded the race in a press conference Wednesday night at the Pullman Hotel, in Central Jakarta. The governor looked visibly saddened by the results as he thanked his supporters for all their help and congratulated Anies and Sandi on their win.

“We want to forget the problems of the campaign period and election day because Jakarta belongs to all of us,” he said. “Our supporters are sad and disappointed, but I am fine. Believe me that.”

It’s a result few would’ve predicted a year ago. Ahok was then riding a wave of popularity as the capital’s no-nonsense leader—a figure who was working tirelessly to rid the chaotic Indonesian capital of the corruption, cronyism, and apathy that had plagued this city of 12 million for decades.

But by the start of this campaign season, the cracks were already starting to show. Ahok was under fire for a series of slum clearing programs that evicted thousands. The evictions, which were meant to clear out communities of “illegal” squatters left many lower-income residents—most of them Muslims—with a sour taste in their mouths.

“I’m anti Ahok,” Kaharudin Misbah, a man who was evicted from his neighborhood in Bukit Duri, South Jakarta, told VICE Indonesia on Wednesday. “He’s Chinese. He can’t lead me. I’m a Muslim. My leader should be Muslim.”

Religion had become a central issue for some voters. Hardline Islamists, who long bristled at the idea of a Christian leading the capital of the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, scored an early win when a video that appeared to show Ahok questioning “Al Maidah: 51″—an Islamic verse that some read as proof that Muslims shouldn’t elect a non-Muslim leader—hit the internet. The video was heavily edited, and Ahok apologized for causing any offense, but the damage was already done.

More than half a million Muslims protested in the streets of Jakarta, calling for Ahok’s arrest. The protests continued as Ahok stood trial for blasphemy. The rhetoric quickly turned ugly as protestors waved signs calling for Ahok’s execution. Others used racially-charged language to describe the governor, a member of Indonesia’s small ethnic Chinese minority that’s long been the subject of discrimination and occasional violence.

Anies Baswedan cheers his victory with running mate Sandiaga Uno. Photo by Beawiharta/ Reuters

As Indonesian media broadcast wall-to-wall coverage of the Jakarta election, it helped raise the prominence of an election that had already grown to become one of the most important races in the country. And with it came supporters and critics from outside the city, including many who were pulled into the fray on religious grounds.

“I came here from Surabaya, as a volunteer for this election so there will be no cheating and so everything goes as well as it should be,” said Dedi, a man from Surabaya who was at a polling station in Tebet, South Jakarta, on Wednesday. “Indonesia refers to Jakarta politically, that’s why the governor has to be a Muslim. That’s for sure.”

It’s enough to leave some Jakartans to wonder whether things had gotten too heated during the campaign season. “Maybe we will need to reconnect with our neighbors after this all passes,” Syakieb Sungkar explained after voting at a polling station in Tebet, South Jakarta. “This election shouldn’t be personal. It’s just an election.”

Others were put off by the election’s divisive rhetoric. “All of this should be a celebration of our democracy,” said Agus Setiadi, in Tebet, South Jakarta. “I don’t really get all the polarizing, radical stuff. All of us want nothing more than to better our general welfare.”

But Anies’ win left others feeling concerned. His secured the early support of hardline groups like the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), an organization known for conducting raids during Ramadan and holding noisy protests outside churches in West Java.

His win may now leave groups like the FPI feeling emboldened, Yohanes explained. Anies will need to publicly distance himself from some of his more radical supporters and stick by his commitment to pluralism if he hopes to head off future problems, he said.

“At first glance, Anies’ win is a win for intolerant groups,” Yohanes said. “This may be the momentum that allows those groups to flex their muscles, especially ahead of the fasting month and Lebaran. Hopefully, this won’t last long and Anies will be firm and support pluralism.”

Members of the FPI were clearly taking Anies’ campaign victory as a win of their own. They were seen parading through the streets of Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta, in a motorcade shortly after Anies announced his win. The hardline Islamists played a central role in organizing the anti Ahok protests and secured a publicized meet-and-greet with Anies before the first round vote.

“Since the very beginning we were sure Anies and Sandi would win,” Ahmad, a FPI member, told local media shortly after his win.

The FPI’s victory lap ended at Jakarta’s iconic Istiqlal Mosque, where leader and self-described grand imam Habib Rizieq invited Anies and Sandi to join them in a show of their gratefulness.

“Later after the Maghrib prayer, we will do the sujud sukur [a prayer of thankfulness],” Habib Rizieq told local media. “Insha Allah, the Muslim leaders who won today will join us.”

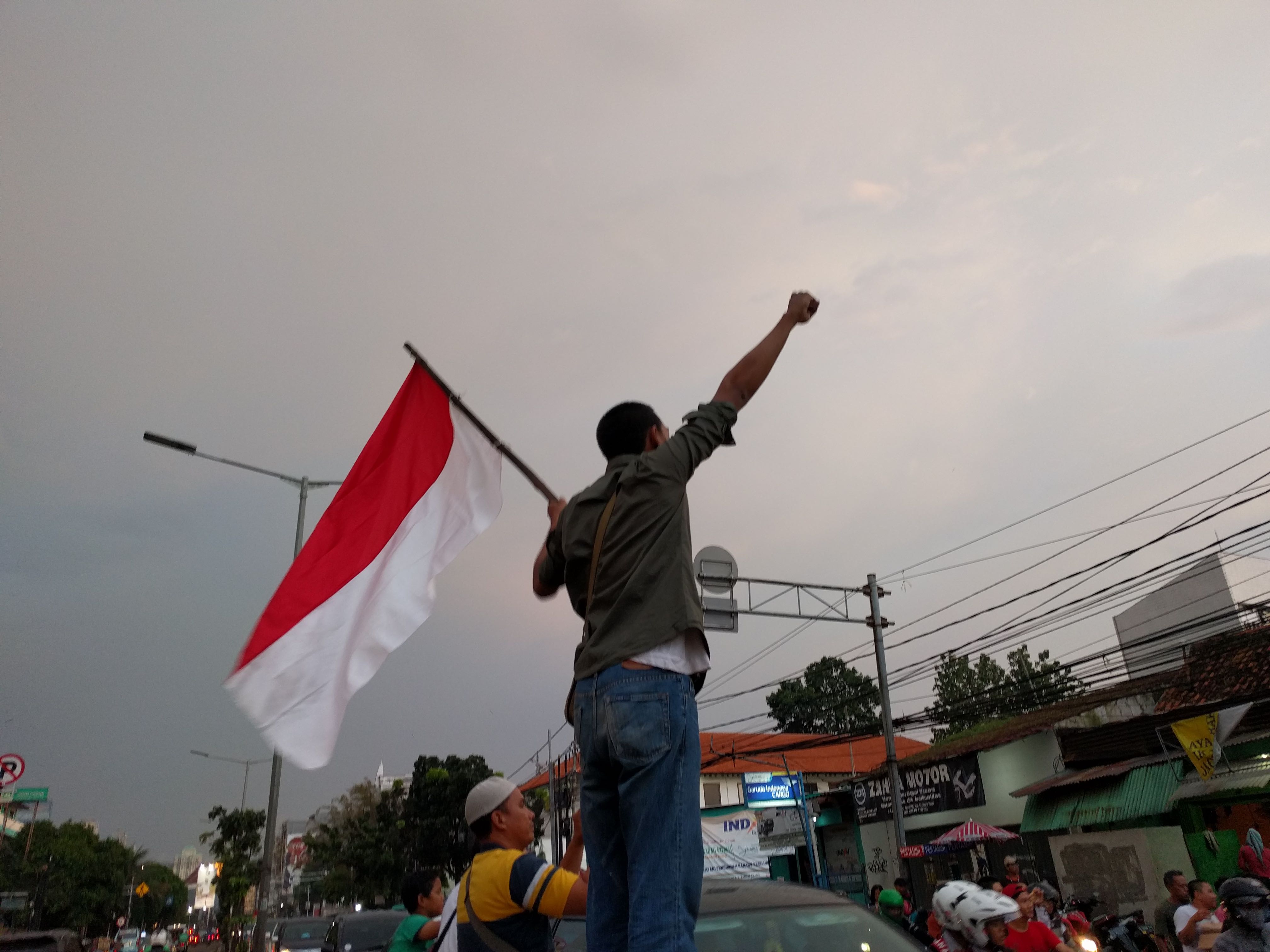

An Anies supporter cheers in Central Jakarta. Photo by Arman Dzidzovic

Still, others questioned the narrative that this election was a test of the nation’s tolerance. Any election is a way for citizens to judge the performance of their leaders, and the results of this election clearly show that Ahok’s version of progress hadn’t served everyone equally, said Siti Zuhro, a political analyst with the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI).

“The election couldn’t be the parameter for the nation’s tolerance,” Siti said. “If you take a look at it, Anies-Sandi do not come from groups with fanatical backgrounds. They’re only looking for the support of Islamic organizations or Islamic parties, and that’s common in politics.

“Tolerance issues are crucial, but they can be managed in time. Jakarta can’t be an intolerant or Sharia city. And Anies-Sandi have denied that they had an agenda to turn Jakarta into a Sharia city. It’s just an exaggeration.”

More

From VICE

-

Samuel J Coe/Getty Images -

Pokemon GO's Holiday Part 1 event 2025 -