If only every day could be like this. You can’t put your finger on why: Maybe you had just the right amount of sleep. Maybe the stars are somehow aligned in your favor. Whatever the reason, you’re cooking on gas. Hours fly by like minutes, you’re feeling great, and before you know it it’s 5:30 pm and your to-do list is done.

This feeling of ‘flow’ or being ‘in the zone’ is something that most of us have experienced at some point or other—although not as often as we might like. It’s a mental state that elite athletes seem to have at their beck and call. For us mere mortals, though, it hardly ever shows up when we need it.

Videos by VICE

Since the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi first described the zone (which he called ‘flow’) in 1975, neuroscientists have been trying to figure out what it is and how to make it show up on demand. Yet as they close in on the secrets of the zone, another truth has emerged: What we think of as the zone is actually one of many mental states that a person can be in, each of which works for a particular kind of thinking. Here’s how to master not just one of them, but several.

The Flow Zone

To understand when other states might work better, it makes sense to first consider what we know about this, the original ‘zone.’ One thing we definitely know is that it feels great: Csíkszentmihályi describes it as the ‘optimal experience’ in which we can achieve true happiness.

One explanation for why it happens—and why it feels so good—is that it represents a perfect match between activity in brain networks involved in attention and the reward circuitry, which process pleasure. When different networks synchronize their activity—like two pendulums swinging in time—it makes the business of thinking run a little more smoothly, which explains why this particular zone feels effortless when you’re in it.

Even Csíkszentmihályi admits, however, that it’s not easy to achieve. “Flow is difficult to maintain for any length of time without at least momentary interruptions,” he wrote—and that was in the 1970s, before smartphones came along and took what was left of our attention span.

So how best to get into the flow? One suggestion is that, rather than screwing up your eyes and trying to force yourself to concentrate, it might work better to do the opposite: Take your foot off the mental gas a little.

This finding came out of brain imaging experiments by cognitive neuroscientists Mike Esterman and Joe DeGutis of the Boston Attention and Learning Lab in Massachusetts. They measured activity in the default mode network (DMN) a collection of brain regions that gear up when we are not thinking of anything in particular. They compared this to activity in the dorsal attention network, which keeps us focused on one thing, and watched how the two fluctuated over time when people were asked to do a boring, repetitive task.

Surprisingly, they found that the best way to sustain concentration wasn’t to cut out DMN activity altogether, but to allow it to carry on as a low-level background hum. In real terms, that means keeping your mind on a long leash: letting it wander a little, before gently bringing it back to heel.

“If you’re devoting all of your resources to a task you will likely be fighting your natural tendency to mind wander. This could actually make sustaining attention more effortful and challenging. If you try too hard you ay actually perform worse work over time,” DeGutis says.

No matter how much you love your work, paying attention for long periods is hard mental work. By relaxing a little, it makes it easier to find the crucial balance of effort and enjoyment that nudges us into the flow. Rather than trying so hard that we set ourselves up to fail, the solution could simply be to stop beating ourselves up.

More from Tonic:

The Slow Zone

Time doesn’t only fly when you’re in the flow. It also flies when a deadline is heading your way and you haven’t quite hit your stride. If time is running short and the flow feels a million miles away, all is not lost. You still have time to master the slow zone.

For better or worse, strong emotions distract us from the passage of time, giving the illusion that it is zipping past unusually quickly. If it’s too difficult to take the emotion out of the equation (that deadline is coming whether you like it or not), the next best thing is to change the way your brain processes the passage of time, to mentally buy yourself a little more.

It sounds too good to be true, but Marc Wittmann, a psychologist at the Institute for Frontier Areas in Psychology and Mental Health in Freiburg, Germany, and author of Felt Time, has a couple of suggestions on how it could be done. Wittmann believes that our brains count time by tuning into the rhythms of the body—the regular ticks of our heartbeat, breathing and so on. He calls this ‘body time’ and points to a region of the brain called the insula, which keeps track of our physical and emotional state, as key to this process.

“My idea is that you are attending to yourself, to your bodily self, your mental self and that is how you attend to time,” Wittman says.

In theory, then, if you can change the information that the insula receives, you might be able to control how you perceive time. One thing Wittman suggests is to speed up your bodily signals by exercising. When you stop, the body’s signals will gradually slow down to baseline, slowing your perception of time as it does so.

“Say I go jogging for an hour and then I’m calm down but still feel very active,” Wittman says. “I feel that everything is happening much slower because my body is much more activated and I feel myself much more intensely.”

Another option is to direct your attention to the here and now, purposefully focusing on the fine details of your surroundings, thoughts or your mental state. A 10-minute mindfulness meditation will help haul your focus back to the here and now and, by slowing your breathing rate, will also slow down your body signals. Both should make time slow to a much more manageable speed. Wittman’s experiments suggest that expert meditators are able to stretch their perception of a moment by 25 percent, which makes all that sitting around seem well worth the investment of time, no matter how little you have to play with.

The ‘Zoned Out’ Zone

Given all the effort we spend trying to get into the zone it might seem strange to actively try to stay out of it. But there are some mental skills that work better when you’re just a little bit away with the fairies. Creativity is one of them.

Research by Evangelia Chrysikou at the University of Kansas has found that using brain stimulation to temporarily reduce activity in part of the prefrontal cortex (the region of the brain behind the forehead), increased the number of creative uses for everyday objects that people were able to come up with. This works because the job of the prefrontal cortex is to narrow down the possible thoughts and behaviors that are suitable in any given situation. This is a crucial mental shortcut because it vastly reduces the time we need to make decisions about what to do or say next. The downside—at least for our creative juices—is that it also reduces the scope of our ideas, making blue sky thinking that much more difficult.

So ideally, the right zone to come up with new ideas is one in which activity in the prefrontal cortex is dialled down a little—a state known as transient hypofrontality. “It’s about using the right tool for the right task. If you want to look for ideas then hypofrontal zoning out will help you,” Chrysikou says.

There is more than one way to reduce activity in the prefrontal cortex. Tiredness works particularly well, so working when you are naturally at your least alert (morning for night owls, late in the day for morning folk and after lunch for just about everybody) is definitely worth a try. A boozy drink does something similar, according to actual studies on drunk students. And if all else fails, sitting in a quiet and/or dark room can’t help but set the mind wandering to who knows where.

However you manage it, it’s worth remembering that while mindfulness is all the rage at the moment, when you want to think creatively, mindlessness is a much better tool for the job. Go on, zone out—your brain will thank you. But remember to come back into the room at some point to make sure that your ideas aren’t too bonkers. “To decide which idea works best, prefrontal involvement is necessary,” Chrysikou says.

The Cramming Zone

There’s nothing like a deadline to focus the mind. It’s almost what the fight/flight response was designed for: A short burst of adrenaline narrows focus to help you ignore everything except the life-and-death task at hand. The trouble is, if a period of stress goes on too long, or happens too often, the whole system breaks down, focus scatters, and takes your ability to concentrate with it.

This is partly because high doses of stress hormones, particularly noradrenaline, interferes with focus by binding to sites in the prefrontal cortex, stopping it from working effectively. Another job of the prefrontal cortex is to help us resist impulses that aren’t necessarily helpful for our long-term goals, which explains why stress can leave you mainlining down tea and biscuits when you should be doing some work.

So, what to do when you are stressed and distracted but need to focus now? One option is—strangely—to make whatever you are doing more difficult to concentrate on. According to load theory, the brainchild of psychologist Nilli Lavie at University College London, the brain only has a limited amount of processing power to use on making sense of the world around us. Her experiments have shown that if you add deliberate distractions to what you are trying to concentrate on (flashing images, colorful borders, background noise) it can actually help you focus. This is because processing these distractions uses up the brain’s processing power, leaving no room to process either external distractions—or your own internal excuses.

This post is partially adapted from My Plastic Brain: One woman’s yearlong journey to discover if science can improve her mind (Prometheus Books, 2018).

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of Tonic delivered to your inbox weekly.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Jorge Garc'a /VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images -

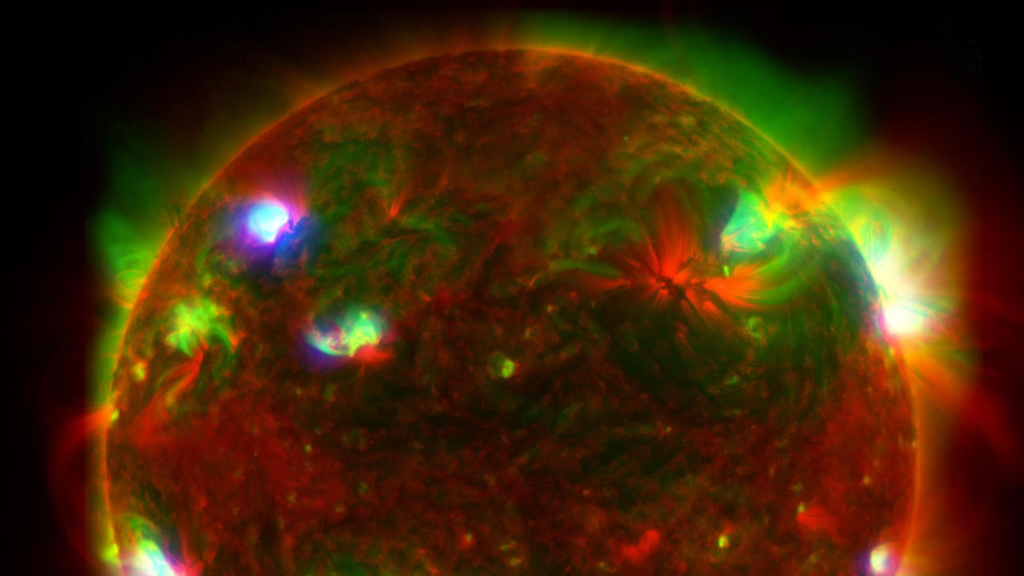

Three-Telescope View of the Sun. Photo: NASA -

Photo: Maria Teresa Tovar Romero / Getty Images -

Photo: grecosvet / Getty Images