Two years and a week after the horrific massacre that left 130 people dead in Paris, the Grand Café Bataclan reopened for business.

On November 13, 2015, terrorists targeted civilians throughout the French capital, including many young Parisians who had been enjoying the unseasonably mild November evening on café terraces. But the worst of the attacks happened at the Bataclan concert hall, where 89 people were killed during an Eagles of Death Metal show.

Videos by VICE

“They went in through the main entrance of the venue,” says new Grand Café Bataclan manager Michel Maallem, who recounts that while the terrorists never came into the café area, “There was a stray bullet that came through [the wall] and hit one of the bartenders in the thigh.” He indicates the wall of the Café, though there is now no evidence of where the bullet penetrated.

After two years of closure, the restaurant, which belonged to the owners of the concert hall until May, has reopened with Maallem at its helm.

“They asked me if I was interested in running the Bataclan… and I thought about it a lot. I had a lot of apprehension,” he says. “I asked the people around me what they thought—my wife, my friends, my family. And they said, ‘Go for it. There’s no reason for you not to. Life goes on.’”

Maallem was present for the five months of work to completely gut and renovate the Café. Its current iteration sports tiled floors, a new mezzanine, and a brightly colored yellow awning taking the place of the black one that once hung here, as well as a few Chinese-inspired details that recall its past: Built in 1864, the Bataclan was named after an Offenbach chinoiserie musicale based in China and entitled “Ba-ta-clan.”

This is all a stark difference from its past iteration: the Café was once more of a beer bar than a restaurant, and the food, according to TripAdvisor reviews, was “horrible,” “disappointing,” or even “a nightmare.”

New Chef Marc Souton’s kitchen, however, is anything but. His experience in four- and five-star hotels is evident, and everything is made by hand and with heart. On the menu, you’ll find simple, hearty dishes such as a house-made terrine, warm Camembert with potatoes, and steak tartare, as well as classic French desserts such as flourless chocolate cake and crème caramel.

“We do everything here,” says Souton, noting that whole ingredients are broken down on the premises (a rarity in bistros and brasseries these days) for house-made food “without fussiness or flourishes” that remains relatively cheap by Parisian standards—a purposeful choice, Maallem says, to make locals feel at home.

Most of Maallem’s current staff was not here the night of the attacks: the former employees, he recounts, hid in the basement side-by-side with customers as they waited in fear of what was transpiring just next door. The only exception, Maallem notes, is one cook who has remained on staff. He is still traumatized by his experience.

But Maallem and Souton understand only too well the weight of the job they have taken on. Maallem was born and raised in the Paris region and has been working in the city for 30 years. The night of the attacks, he was working at a Marais restaurant, less than a mile from the Bataclan.

“The restaurant was full,” he recalls. “Someone told me that something was going on in the 11th arrondissement, but I didn’t really get it. And then as time went on, people started to panic a bit.”

He lost a former employee that night: a young man in his 30s who had been spending his evening at La Belle Equipe, one of the other nearby restaurants targeted by the terrorists.

“He was at a sidewalk café, having a drink… and voila,” says Maallem.

Souton meanwhile, remained in the dark until the end of his shift at Habemus, a restaurant near Paris’ opera house. “It was traumatizing,” he says. “And a little unreal.”

He recalls that his former boss refused to let anyone go home via public transport and called individual taxis for each employee.

“We didn’t know what was going on,” he says. “People were saying there were still armed men in the streets. Everyone was afraid.”

When Maallem offered him the kitchens at the Grand Café Bataclan, however, Souton didn’t hesitate for a moment. “It’s an adventure I accepted gladly,” he says. “It’s an honor to be part of this sort of project, to bring a place that’s been part of Paris’ history back to life.”

Today, the Bataclan shootings are part of the collective memory of the city and its residents; this, perhaps, is why Maallem didn’t feel the need to give his staff any particular guidelines with regards to what to expect at their new job. “They know the story,” he says. “They’re Parisians, too.”

Even Chef Souton, with his Southern lilt stemming from his upbringing in Aveyron, feels that the event has united the residents of the capital—and he counts himself among them. “You don’t think about it every day, but you think about it,” he says. “It’s part of us now.”

Of course, this doesn’t make the job easy. Maallem notes that confronting the memory of the massacre every day can be oppressive. “Even when we go home, we think about it,” he says. “There were a lot of deaths right next door.”

Despite its makeover, the Grand Café Bataclan has also become a de facto place of mourning for people still haunted by the events.

“There are clients who come in and pray,” says Maallem. “There are clients who cry, there are clients who confide in us, who tell us their stories, like a kind of therapy.”

He gives the example of one afternoon, soon after the restaurant reopened, when an informal commemoration was held for a young man killed at the Bataclan. “An entire family stayed here all day,” he says. “And there were comings and goings of who I imagine to be cousins, aunts, nephews… all day, until 10 PM.”

The Bataclan reopened for concerts on November 12, 2016, the night before the one-year anniversary of the attacks. Since the Grand Café’s reopening, the symbiosis between the Café and the concert hall has reestablished itself: concert-goers and locals have become staples at the restaurant, and Maallem has even started organizing small music nights at the Café itself, inviting local bands to play. “Last week we had a gypsy jazz group; next week we’ll have music from Latin America,” he says. “We try to bring the space to life, to brighten it up, for better or for worse.”

Tourists, too, have become frequent visitors. A staple of their photo shoots is the imposing two-dimensional laser cutting on the wall, a piece by Norman artist Marc Dupard. In it, a young couple kisses; the man in a baseball cap and sports jersey, the woman in a shirt covered in flowers.

“It had to represent love,” says Dupard. “And at the same time, since this has unfortunately become a legendary location, I didn’t want it to be too commemorative.”

He titled his piece Génération Bataclan.

“I wanted to represent a couple of this generation,” he says. “One that has been subjected to all this violence and that nonetheless continues to live.”

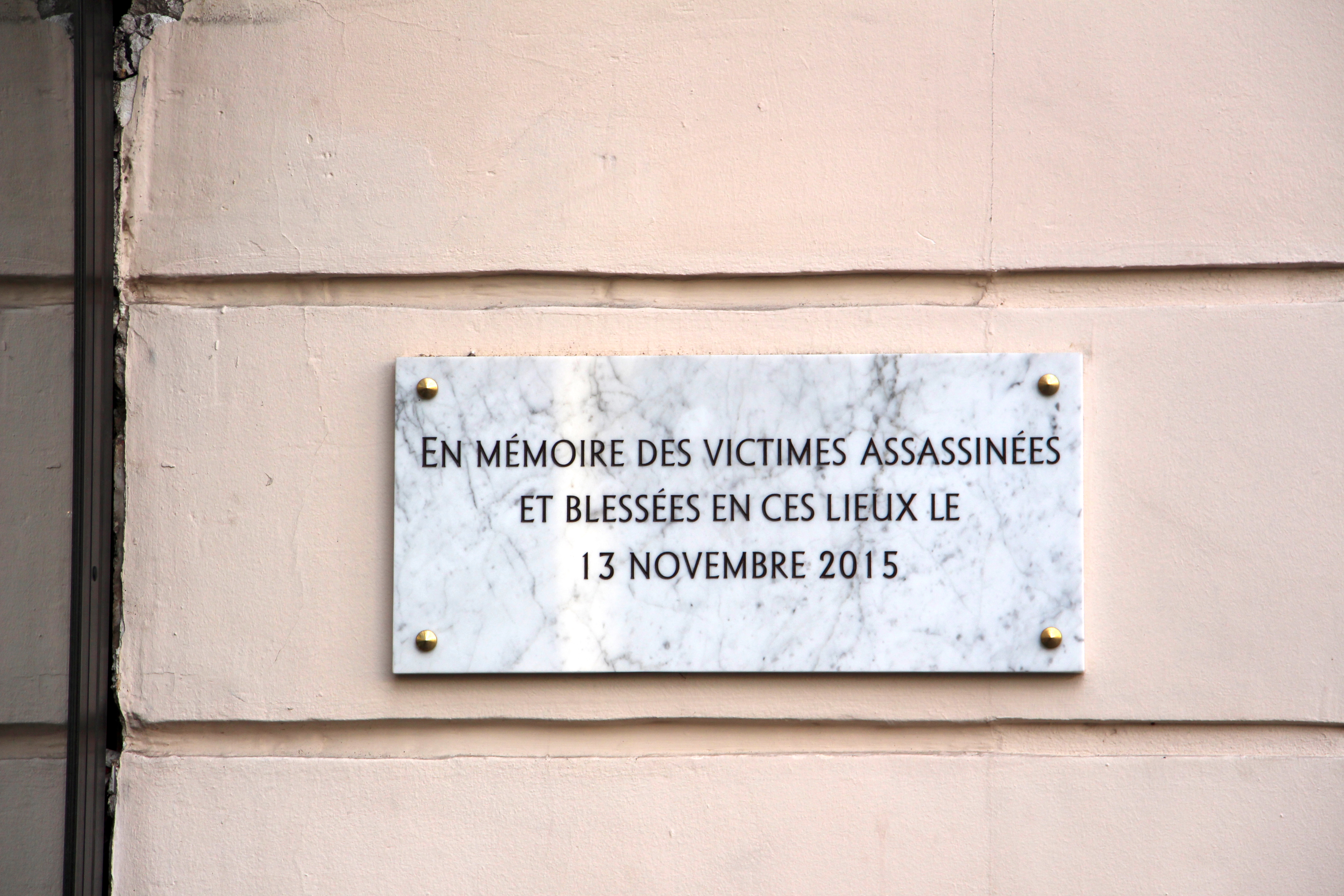

The visible evidence of that night in 2015 is gone. Gone are the posters that once adorned nearby Republic Square, gone are the bouquets of flowers, the candles. All that remains is a small plaque on the wall between the Café and the concert hall. But Parisians have not forgotten.

“There’s a lot of solidarity,” says Maallem, recalling the people who came by in the first week of the Café’s reopening, just to say “thank you.”

“I think that Parisians are traumatized, but at the same time…” he searches for his words. “They haven’t put it behind them, you can’t say that, but they’re moving forward.”

Despite the history that casts a shadow over the Grand Café Bataclan, it’s clear that both Maallem and Souton have an enormous amount of pride and love for the work they are doing here.

“Sometimes I come out of the kitchen to see our regulars, to see how things are going, and things are always going well,” says Souton. “There’s no secret. I have a great team. We work with a smile, with a good mood, and the clients can feel that.”

After all, this is perhaps the best method of protest: As a counterpoint to 9/11, to which these attacks were so often compared when they first transpired, terrorists in Paris targeted not the financial center of the city, but its buzzing nightlife.

“They explained that, why they targeted this place,” says Souton. “Because it wasn’t good: it wasn’t good to be with your friends, to have fun, to laugh, to drink alcohol.

“But that’s part of our culture. It’s part of our French identity. It’s part of the culture of good food and good wine.”

More

From VICE

-

fStop Images /Caspar Benson/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Nintendo -

Photo by Jason Edwards via Getty Images -

Screenshot: Ubisoft/ Vivendi Universal Games