All this week on Noisey, we’ll be falling arse-backwards into the state of UK music in a special series of articles about scenes outside the capital: from club closures to brain drains to free parties to local legends. Follow all the content on our Fuck London hub here.

In the early 90s, my friend and I would sneak into his older brother’s room to find the curtains drawn, blacking out the grey suburbs, with the only light coming from a lava lamp bubbling away in the corner of the marijuana-scented den. We’d tune in to Kool FM, carefully remove happy hardcore and jungle records from their sleeves, and gaze up at the dozens of rave flyers covering the walls. Raindance, Fantazia, Tribal Gathering, Exodus, and other distant places that him and his mates would drive out to in a Ford Orion with ripped holes in upholstered seats. M25 raves in deepest Essex and Hertfordshire where loved up summer nights would become velvet summer mornings. We were in our early teens, and it was the closest we could get to experiencing our elders recreational delights. I couldn’t wait to see more.

Videos by VICE

Ten years later, approaching the millennium and engulfed in the ennui of Blair’s New Britain, it was our turn. In the wake of the Criminal Justice Act – which had rendered all unlicensed gatherings illegal, particularly if they involved soundsystems blaring out techno at 4am in the middle of green belt land – an entirely different, more complex free party scene had emerged.

We started in London – in cavernous disused meat factories in Tottenham Hale with leaking ceilings and ten soundsystems pounding out gabba and drum and bass, or condemned office blocks in Shoreditch where every floor was a different party. A realm where the central stairwell would be jammed with youngsters chewing their inner cheeks, unable to decide which room best suited their level of high. But the London scene quickly started to turn. The dark rooms where we would go to seek adventure turned into a monstrosity – full of questionable characters.

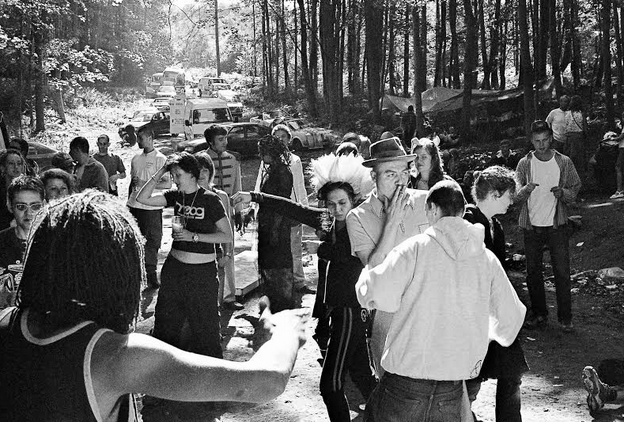

A rave held at Goodwood in Sussex.

“There were reasons I’d stopped going to London raves”, Molly Macindoe – who has released a book documenting the scene from 1997-2007 – tells me. “London goes through dark phases. Once a bad crowd who has nothing to do with the raving catch on, they might get hold of the phone line numbers and you’d find crowds of bad people coming to a London party to make money robbing ravers.”

It wasn’t just outsiders bringing the bad vibes into London either. Those inside the scene were introducing the “brown acid” in the form of ketamine. The loved up ecstasy moments where you told your best mates how beautiful you’ve always found them were being replaced by more squalid scenes. At one event our entourage carried on partying the night away while one of our school chums, dressed in a wizard’s hat and trenchcoat, lay face down on a grimy concrete floor for hours – deep in a K-hole. The community vibe in London had turned dark. It was time for a change. So the parties started to spread across the country.

“The rig owners got together to figure out what to do about it and decided to change things,” Macindoe told me. “London had a not very nice vibe and I really enjoyed the different vibe in the countryside. It filters people out, you get more determined people coming to the outdoor ones as they’re harder to get to. And, it’s a bit cheesy, but the sun comes up and you’re looking out over the beautiful English countryside and rolling hills.”

Outside of London’s dereliction, the party people and their new age sound-systems began to find their way across the home counties, South West and Wales. The first rave explosion outside of the capital took place around the new millennium’s first summer, kicking off on a picturesque, 5,000 year-old site on one of England’s oldest roads – the Ridgeway in Oxfordshire. Three soundsystems played at the Lord Wantage Memorial – an idyllic spot on the 87-mile stretch – in June 2000: Agro (from Berkshire) Headfuk (from London) and Survival (from Buckinghamshire). Soon, other places were getting involved. The next month saw Technonotice (from Bournemouth) and K.D.U (from London) take over an abandoned Farmer’s barn in Gloucestershire. Over the following decade, everywhere from the Davidstow Airfield in Cornwall, Bude in Devon, the Dartford Tunnel in Kent and Abergavenny in Wales hosted debauched throwdowns in fields. It was a brand new scene, not exclusive to London, but taking place in dilapidated downs, disused warehouses, and factories across the country.

A rave on the Ridgeway.

The Ridgeway was a go-to place for parties because it’s located along the county borders of Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire in a jurisdiction loophole. But, unlike the original acid house movement, the free party scene involved locals as well as Londoners.

Roxy Fielding, who now lives with her husband and young son in Ibiza and co-manages Vinyl Carvers, a company that makes dubplates, was born in London and moved to Oxfordshire in 1997 at the age of nine, growing up just 10 miles from the famous Ridgeway party point. It was a total culture shock. Fielding moved from London’s multicultural Finsbury Park to a tiny Tory-level village called Benson in South Oxfordshire – which, by comparison, offered nothing for young people. Until she discovered the secret world of the free party scene.

“I never really felt part of life there and I never felt a connection with the place before I entered the underground free party scene. It was pretty spectacular. Parties were on every weekend and huge convoys of all sorts of people would go to them,” she tells me on the phone from Ibiza. “Everyone who didn’t lead a completely sheltered life knew about it. It was what the alternative kids did. It was something that belonged to us.”

Drum and bass was hugely popular in smaller towns and cities throughout England in the late 90s and the Oxford that Fielding discovered was full of record shops dedicated to dance records and tapes of Helter Skelter and One Nation raves. But the mainstream ravers who could get their records into shops hosted events that were inaccessible to youngsters. “We couldn’t get into nightclubs and even if we were old enough they were far too expensive, restrictive, and a breeding ground for idiots on the pull or looking for a fight,” says Fielding.

The Free Party Scene was inexplicably different from a nightclub. There was no dress code, for a start. Then there’s the giddy excitement of illicit activity and the “come one, come all” spirit.

Like your first fag in the school loos or your first bungled attempt at shoplifting, the adrenaline was part of the rush. Instead of standing outside a bus-stop shivering in the rain, you would walk toward desolate reservoirs or marshes toward the imposing silhouettes of power stations. The address would come from 0909 party lines that connected you to a recorded message giving directions. There were no bouncers. Instead, a man – usually half punk, half new-age traveller – would hold a bucket full of coins and gruffly encourage a donation. It was an entirely different world.

Inside you would find all sorts of species. Forty-year-old men in cowboy hats and huge clumpy space boots jerking weirdly to gabba. Girls with devil horns styled into their crew cuts. Anarchists. Classic dreadlocked-white rastafarians. Lads in adidas tracksuits and bumbags. It was about as close to the characters in an Irvine Welsh novel as you’re likely to get.

Fielding remembers her first epic three-day party in Wales when she was just 14. She’d told her parents she was going camping with friends and drove across the border in the “Girlie Car” (a little white Vauxhall Nova) with four girlfriends, two of whom were dating guys from a big soundsystem.

“It was meant to be a massive party,” she recollects, “but by the time we got to the Black Mountains the police had cottoned on to what was happening and blocked all entrances to the party. All the rigs who couldn’t get in set up another party not far from the original site. There must have been eight sound systems in the end. A fairly monumental party. The sound system we had gone up with couldn’t get up the hill quick enough and the police escorted them to Hereford. And of course, once they were in Hereford they found a spot, got their rig out and set up a party there.”

Fourteen years on, she still considers a lot of the people she danced across the countryside with as some of her closest friends. They’re kindred spirits, really. They would arrange hundreds of crates of beer piled in a makeshift bar area for £2 a can, somehow transferred the equipment into a field and got it working, and they it all on with no financial backing, no sponsor, no marketing and no entrance fee except a few quid. But eventually police powers – especially anti-terror laws – made things difficult. The influential people who made the scene fantastic and found the best venues didn’t want to carry on anymore, and some had day jobs and families to attend to.

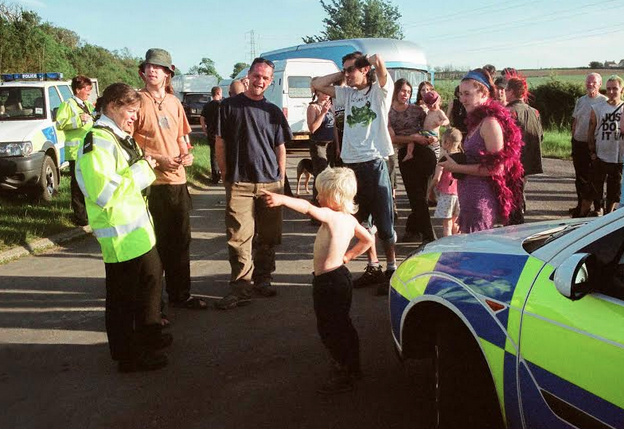

Some police looking less threatening at a rave in Somerset.

For a lot of the original free party massive the police battles became too frequent, too stressful and in some cases too violent. The bad police busts began to stand out more vividly than the memories of the sun coming up over a field of sunflowers while ravers in fancy dress wound things down by dancing to disco tunes. Police set up roadblocks to prevent convoys of cars accessing sites. Ravers arriving by night would often find themselves on foot clambering across fields following the light of the police helicopters. It had become a parody of the illustration on the inside sleeve of the Prodigy’s Music for The Jilted Generation.

Two years after the Free Party Scene had exploded across the country, it became more threatening than fun. “It was so dangerous I thought I’d be found in a ditch”, Molly tells me, recounting a rave she attended to protest the abolition of Glastonbury’s free travellers field in Devon, in 2002. “The police tricked us into crossing a field on foot in the dark, leaving our cars parked up, then they chased after us with torches. We got to a hedge which I got through, but my friend got grabbed. I’d left my phone, lighter and torch in the car and I had to get down commando-style to avoid the sweeping police lights. I’d brush against electric fences and then I found myself in a barn with hundreds of animal’s eyes looking at me, I fell in a ditch full of nettles and eventually after an hour I got to the party and there were thousands of people all with similar experiences to tell”.

A rave held this year in Bristol.

The scene never ended though. Like everything that’s been invented, it returns in cyclical fashion with a new, younger generation, yet to be tainted by police search lights. Molly attended two parties in Avonmouth, Bristol last summer – and there’s currently a host of soundsystems active in the area. Kaotik, BBL, OCD, Irritant, Subliminal and Tossers, to name a few. But sadly many raves are still shut down before they’ve even begun and kettling, arrests, and equipment seizures are part of the recreational hazards.

“It’s not as if the police don’t know the names of the rigs anyway, people are using Facebook to get the crowds in,” she says. “But a lot of rigs have started to realise social media is not a good way to go and they just do it by text message. Very old school.” It’s interesting when you think about the lineage from the M25 raves of 1988 and the modern thing it’s become. The acid house days still inspire the modern crews and the traditions are all roughly the same, although sat nav means you don’t get lost as much these days.

“There’s still that excitement of passing by another car full of ravers then ending up in a convoy and everyone decides you know where you’re going so they all follow you and then you have to turn round,” Macindoe says, smiling wistfully. “And when you do finally get to the position where you’re waiting in the dark, you’ve got past police roadblocks by climbing hedges and electric fences to get to a rave and then it happens… that’s a real thrill.”

You can follow Josh on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: PlayStation -

Jamie Cooper/Contributor/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Bandai Namco -

LIONEL BONAVENTURE/AFP via Getty Images