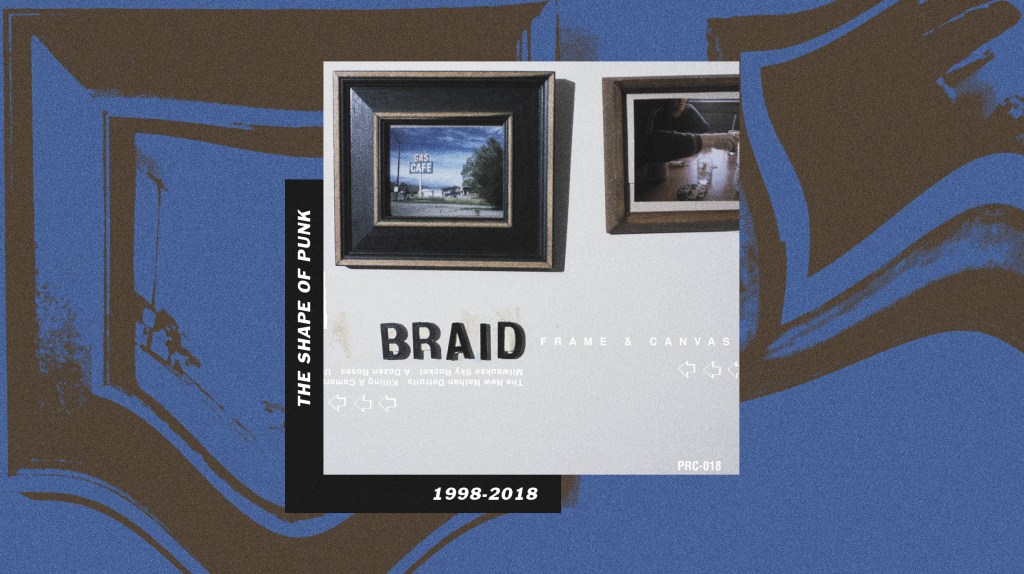

The Shape of Punk revisits some of the seminal albums turning 20 years old in 2018, tracing their impact and influence on the future of the scene.

By the early 90s, emo was starting to gain a foothold in the underground punk scene. Across the United States there was a surplus of bands using Rites of Spring and Embrace as their jumping off point, spawning new subsections of emo in their wake. For as popular as the genre was becoming, only certain bands were plucked out of obscurity and given a second life, usually long after they’d broken up. For every Cap’n Jazz, there were at least a half dozen other bands that would exist seemingly to be forgotten, sometimes because their music didn’t measure up, and other times because they got lost in the flood of emo records being released by upstart labels. And if it wasn’t for Frame & Canvas, Braid might have easily become one of those bands—a mere footnote in the emo history books.

Videos by VICE

From the very beginning, Braid was an ambitious band—even if they weren’t sure how to harness it right away. Formed in 1993 when former Friction drummer-vocalist Bob Nanna left Chicago to attend college at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, Braid would go through several line-up changes before settling into the band people came to know. Founded by Nanna, who ditched the drums for guitar, and drummer Roy Ewing, the pair had connected in a way so many bands did at the time: through an ad in Maximumrocknroll. The pair was interested in trading bootleg VHS tapes of live shows, and when Nanna landed in Champaign, Ewing’s hometown, it made sense they’d start a band. Once they rounded out the line-up with bassist Todd Bell and guitarist-vocalist Chris Broach, Braid would get to work on a prodigious introduction.

Nanna floated a wild idea for the band’s debut album, Frankie Welfare Boy Age Five, and the band delivered on it. The idea was to write a song whose title started with each letter of the alphabet, which meant Braid would have to write 26 songs for their debut album. With each member curating their side of the vinyl release, the band effectively remade The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime, stuffing four sides of vinyl full of songs that were sandwiched between samples of radio static and other found sounds. It was a mess of an album, but when sifted through, there were a handful of gems worthy of extraction.

By the time Braid released The Age of Octeen a year later, they’d learned how to turn their outsized ideas into something more nuanced. This jump in quality was brought on by the fact that, although they weren’t writing for a sprawling double album, they never slowed their output, writing songs at a feverish pace and throwing them at any split single or compilation they were offered. “Good comps, bad comps, any comp; just give somebody a song,” Bell said in Eric Grubbs’ book Post, which focused a chapter on Braid. It was a strategy that was of its time, as the band dashed off song after song, often giving them to labels so obscure you’d have had to be a devout Braid fan to have heard them. But this approach allowed Braid to refine itself rather quickly. Those obscurities would be compiled on the two-volume collection Movie Music, showing Braid’s evolution from a ratty little post-hardcore band into the midpoint between bands like Jawbreaker and Fugazi.

The band recorded their third album, Frame & Canvas, at the famed Inner Ear Studios in Arlington, Virginia, with Jawbox’s J. Robbins in December of 1997. Released on April 7, 1998, it was immediately apparent the album was the best full-length statement they’d made. Though Ewing had left the band after the release of The Age of Octeen, Damon Atkinson proved to be the perfect substitute for Ewing’s jazz-flecked approach to punk drumming. On opening track “The New Nathan Detroits,” Atkinson introduced the song with a complex, mathy drum intro, one that saw him show off his skills by literally hitting underneath his drums, as he swung his arm around to hit the underside of his hi-hat cymbals. Once the rest of the band jumped in, Nanna and Broach showed their growth as songwriters, more capable of distilling their influences into something that became their own. Their riffs sounded almost oppositional, with each guitarist nestled in their own channel, creating a uniform sound by allowing space between them, enough for Bell to rush headfirst up the middle.

Frame & Canvas looked unassuming on its face, but the record showed the most marked evolution of what emo would become just a few years later. Where Braid started out as a louder, more hardcore-fueled band, Frame & Canvas put a premium on hooks, with nearly every song starting with austere, off-time riffs that dovetailed into a full-on sing-along. Songs like “Never Will Come For Us” and “A Dozen Roses” showed Braid’s ability to soften their attack, allowing songs a bit more breathing room so Nanna could dash off tongue-twisters without having to spit them out a mile a minute.

Yet, for its introspective turns, what made Frame & Canvas work was how outright fun it sounded. “First Day Back” leapt out of the speakers with the kind of giddiness of kids running out the doors of their classroom on the last day of school. Pair this with Broach’s emphatic yelps of “Yeah!” tossed in, and the song had its own jagged exclamation points built right in. The band would use a similar template on “Milwaukee Sky Rocket” and “Ariel,” two songs that showed Braid’s ability to dash of ebullient songs that proved their punk spirit remained firmly intact.

While Braid’s songwriting hit a new peak, as evinced by album closer “I Keep a Diary,” Robbins’ production was noteworthy in its own right. Until then, Braid’s recorded material had always felt like a means to an end. For as solid as songs on The Age of Octeen were, the drums were shrill, and the guitars were chunky in the way so many early emo albums were, as no one seemed to know how to properly engineer all the quiet-to-loud transitions. Frame & Canvas gave everything a bit more gloss, but in a way that felt earned, making Braid sound like a band that could have been on Dischord instead of one on Ebullition.

But as Braid was refining their musical approach, a new set of emo bands had come up behind them. Milwaukee’s The Promise Ring had taken the jangle of 60s pop songs and supplanted them with open tunings, while Kansas City’s The Get Up Kids—who Braid took on their first tour—were effectively removing the hardcore root that ran beneath emo since its genesis. In that way, Braid fell in a space that was more akin to indie rock, even if their time spent working within emo’s knotty framework all but walled them off from that scene. And as these newer bands were on the rise, Braid had run themselves into the ground.

In addition to not making anything resembling a sustainable income—”It’s pointless to play if you don’t get paid” they cheekily declared in “The New Nathan Detroits”—the band’s seemingly endless touring cycles all but dissolved their personal relationships. After attempting to record a new set of songs, it became clear the band was fraying apart, and in August of 1999 they played five final shows in the Midwest. Nanna, Bell, and Atkinson would form Hey Mercedes shortly thereafter, while Broach worked on assorted projects like The Firebird Band and L’Spaerow.

In 2004, after a few years apart, the band repaired whatever relationships had soured, and with breaks in the touring schedules of their new projects, they decided to go on a sort-of reunion, sort-of farewell tour. In those scant five years, it became clear how Braid’s sound had been sucked into the burgeoning third-wave emo scene. Though their closest sonic foil was, fittingly, Hey Mercedes, other Midwestern bands were beginning to show respect to their forebears. On Fall Out Boy’s breakout album, 2003’s Take This To Your Grave, they’d name a track after Grand Theft Autumn, the label that Bell had run and had released some of Braid’s best singles. “Grand Theft Autumn/Where Is Your Boy” could have seemed like just a coincidence given the band’s penchant for wordplay, but when Pete Wentz was found doing his own version of Broach’s energetic “Yeah!” in the verses, it was clear that Fall Out Boy were students of Frame & Canvas.

While Fall Out Boy were always prone to making their references more overt, Minneapolis’ Motion City Soundtrack were more sly about it. On 2003’s I Am The Movie, the band’s Braid worship was already noticeable, but they’d draw a more clear line back on their Mark Hoppus-produced sophomore album Commit This to Memory. Motion City was more inclined to play fast and loose with their influences there, swiping a Promise Ring lyric for “L.G. FUAD,” and in the midsection of “Time Turned Fragile” drummer Tony Thaxton used Atkinson’s drum pattern from “The New Nathan Detroits” as the launchpad for the entire back-half of the song. It was a clear nod to Atkinson, and also a makeshift audition, as Thaxton would later fill-in for him on a UK tour after Braid reunited again in 2011.

Once Braid fully reunited, they’d enter a world where bands spoke of them more effusively and were less shy about using them as an influence. Throughout the Midwest, bands such as Grown Ups and Coping were working on their own blend of punk-leaning emo, and by the time the “emo revival” was getting mainstream press coverage, the sound of Frame & Canvas had become so foundational it was hard to find a band that didn’t have a bit of Braid in them. Unfortunately for Braid, even with the release of the great reunion album No Coast, they weren’t imbued with the cultural cachet of bands like American Football, with Braid having fallen dormant in the years since its release.

That’s apropos of Braid’s entire career, as they were always a bit ahead of the curve. Frame & Canvas predated emo’s mainstream breakthrough, and their reunion started years before cultural gatekeepers were willing to entertain the idea of emo as a valid artistic pursuit. Instead, Braid remained in their own space, doing the work for themselves and committing those efforts to record. For a band that ambitious, the work was the reward, and Frame & Canvas was a distinction unto itself.

David Anthony is on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Bethesda, Nintendo -

Screenshot: Steam -

Screenshot: Sony Honda -

Screenshot: Epic Games