When my mother visits, tensions rise over what I can only describe as her cavalier handling of raw meat.

Her methods at the counter have caused me to question how I survived my childhood. I can’t shake images of her bare hands gripping raw chicken pieces; dunking them in egg, flour, and breadcrumbs; lowering them into the pan; then wiping her fingertips on my kitchen towel. I turned away when I saw her reach for the utensils to set the table, as I might have ended up in the fetal position under it.

Videos by VICE

Years ago, I had the misfortune of watching an investigative report, the sort that reveals more on a topic than one ever should know. A chicken was covered in a substance that would illuminate in fluorescent light. After a woman prepared the chicken, the light revealed the bird’s sinister bacterial essence on almost every surface of her kitchen, from the cabinet knobs to the bananas to the rim of the dog’s water bowl. Perhaps I watched it at a particularly impressionable age—I think I was 26—but it forever changed my relationship with raw chicken.

Since then, when making a chicken dish, my most looming challenge is to prevent a bacterial catastrophe. I wash my hands not just before and after the prep, but several times in between, at each inkling I’ve been in direct contact with the poultry or its packaging. I turn on the faucet with my elbow (praise be the single lever) and open the oven with my toes. I have a meat-only cutting board. (My mother used it for salad.)

When I make her breaded chicken, my husband is shocked and awed by the number of utensils I must use to get the chicken dunked, into the pan, turned, then removed to serving plate with zero finger contact. If I lose track of which fork touched the chicken raw, I take out a new one. It can easily take seven forks to get the job done.

I view cooks on TV with both envy and suspicion. So deft is their handling of proteins as they produce their feasts. Surely, it’s the power of editing that hides the hand-washing and utensil changes. Are these bacteria-aware moments simply piled on the cutting room floor??? (This is what I yell at the screen when I watch Top Chef.)

I know I’m not alone. One friend keeps a jumbo box of hospital gloves in her kitchen for handling raw meat. Another obsesses that the spatula used to cook meat cannot be the one to serve it. Her boyfriend, however, does not agree, and they have argued more about this than his forgetting to put on a new roll of toilet paper.

Sussman admits that our current culture has us running scared from bacteria. But she helped me recognize that the ugliest things that have happened to me or someone I love that involve bacteria have not involved a meal made at home.

My husband once approached me with an issue of Consumer Reports. “You might want to read this,” he taunted. When I saw the cover photo of a package of chicken wrapped in yellow caution tape, I told him to leave the room and take his magazine with him. Enabler!

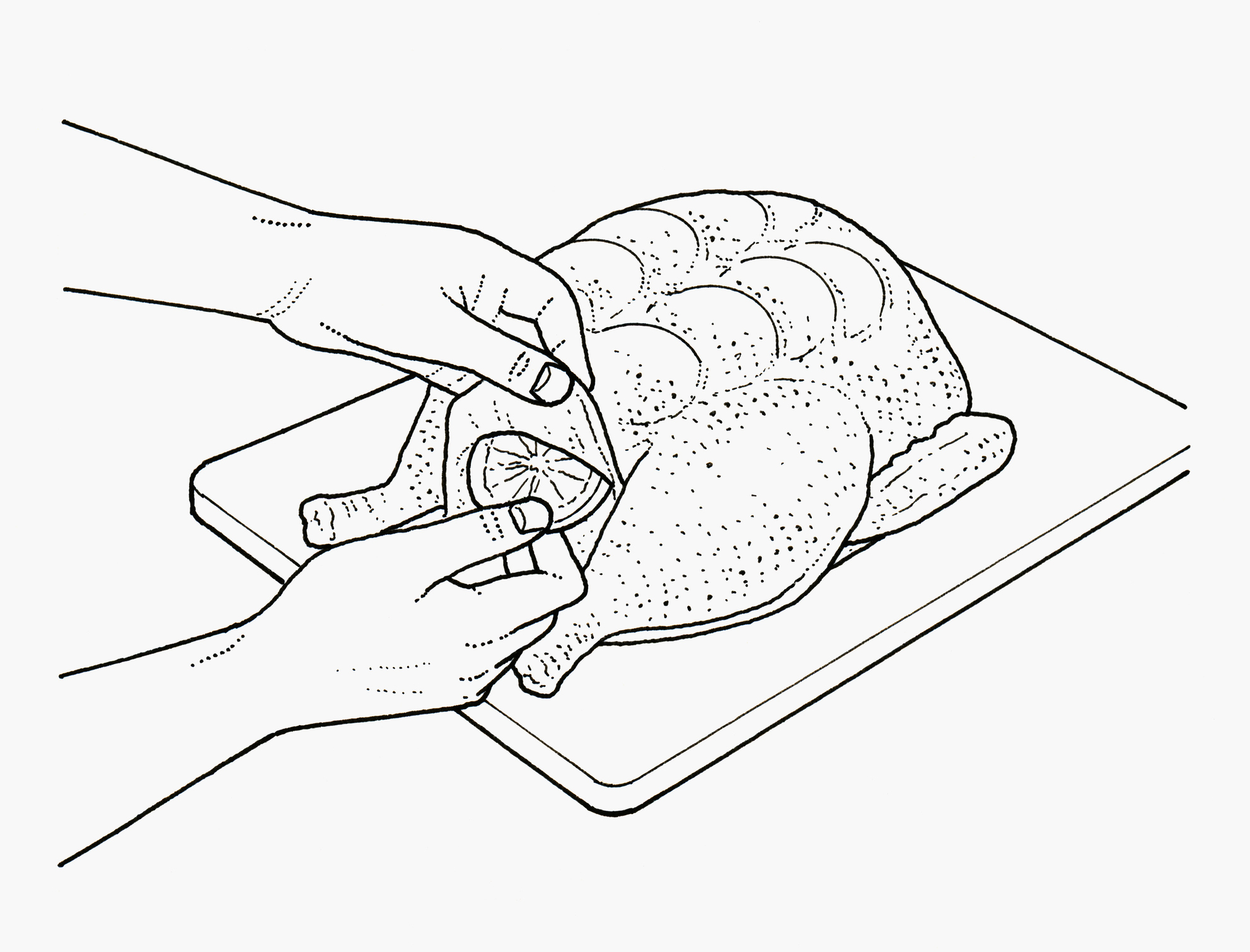

Over a glass of wine, I confessed my raw meat anxiety to my friend Natalya. Then I confessed I had a whole chicken, impulsively purchased the day before, sitting in the refrigerator. I had been paralyzed to do more than move it there out of the grocery bag. Natalya jumped up, grabbed the bird out of the fridge, and had it stuffed with lemon and onion, hand-rubbed with I don’t know what, and in the oven before I could say, “Please don’t wipe your hands on my tea towel.”

An hour and a half later, we sat at the table with the chicken—perfectly roasted—between us. We used our hands to pull it apart, the warm meat melting in our mouths. No plates, no utensils, no fear.

Knowing it could be like this, I yearned to live my life in the kitchen differently, to stop quaking in my apron and cook not afraid.

I sought professional help.

Adeena Sussman, co-author of Fried & True, not only knows her way around a chicken, but hundreds and hundreds of chickens. I prepared to receive from her the zen art of raw-poultry maintenance. I was disappointed.

Sussman is indeed relaxed in her kitchen with raw chicken. But she does think about it. She prepares her dishes near the sink so it’s easier to wash her hands. She pays attention to where her hands are in the chicken-juice-space-time continuum. When it comes to bacteria, she’s no alarmist, but she is a realist. “There is a happy medium between a barrier of fear and your ingredients,” she counsels.

“We are crawling with bacteria!” he basically yelled at me. “A healthy adult will not die or get sick from exposure to a little chicken juice. We are so afraid of bacteria and germs. The media bombards us with misinformation. They don’t tell us the odds.”

Sussman admits that our current culture has us running scared from bacteria. But she helped me recognize that the ugliest things that have happened to me or someone I love that involve bacteria have not involved a meal made at home. I once ate a chicken shawarma from a cart outside the New York City courthouse when I was on jury duty and spent the next two days horizontal on a bench. My husband ate bad shrimp at a corporate cafeteria and couldn’t look at crustaceans for years. My mother- and brother-in-law ate bad sea bass at a wedding reception. (The rest of us were fine; we’d had the chicken.)

Still, what more could I learn to keep calm cooking at home? Sussman put me in touch with Michael Ruhlman, who wrote the book Egg. (In my case, the chicken came first.) Ruhlman is comfortable with bacteria in a way I found both shocking and liberating.

“We are crawling with bacteria!” he basically yelled at me. “A healthy adult will not die or get sick from exposure to a little chicken juice. We are so afraid of bacteria and germs. The media bombards us with misinformation. They don’t tell us the odds.”

I told Ruhlman I was on a quest to handle raw chicken without overthinking my every move. He described a date with a bird in his kitchen. He rinses it in the sink without worrying about “chicken splatter.” He uses a wooden cutting board that just might be used to chop vegetables another time. And, knowing this would be hardest for me to hear, he picks up a knife with his “yes, chicken-y hands” if he needs to cut it into pieces. When the chicken is in the oven, he washes everything with hot, soapy water and leaves it to dry.

As always, people who worry less are an inspiration to those of us who worry too much. Maybe I’ve been giving raw chicken too much power?

“Relax,” Ruhlman ordered. “Use your common sense. Handle your chicken with care, not fear.”

I’m working on it. Less hand-washing. Fewer forks. Some self-talk. The odds keep showing me that bringing people to the table for a home-cooked meal is always worth it. And in a game that involves chance, the player I want to focus on is dinner.

More

From VICE

-

-

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA – NOVEMBER 14: Timothée Chalamet seen at a Special Screening of A24's "Marty Supreme" at Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on November 14, 2025 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Eric Charbonneau/A24 via Getty Images) -

Photo: Gandee Vasan / Getty Images -

Photo: duncan1890 / Getty Images