Header image courtesy of Weird Reality Symposium.

Evangelists of virtual reality believe it creates the ultimate empathy machine—this idea was wildly contested at the Weird Reality symposium this past October. The weekend-long event showcased independent and emerging voices in virtual reality, departing from typical tech fantasies and normative corporate media.

It’s far from the world’s largest VR expo in terms of scale, but I was surrounded by a diverse group of critical thinkers who gave me a fresh perspective on how to use virtual reality to engage with the emotions of others. I learned that what makes virtual reality special is that it is never a passive experience. From where we direct our gaze to what challenging decisions we make, VR asks us to participate. The agency it gives us allows us to have a conversation with the experience—this is where the magic happens.

Videos by VICE

Weird Reality was an “unconference” and exhibition. The day involved bouncing around Carnegie Mellon University between workshops, talks, and panel discussions, while by night I found myself in a repurposed ballroom at Pittsburgh’s Ace Hotel flanked by a row of people in headsets, while music bled into the room from the concurrent VIA festival.

In this “VR Salon” some people queued up to play Kokoromi’s Superhypercube, while others sat on toilet seats to enjoy Laura Juo-Hsin Chen’s communal bathroom experience PoopVR. The VR Salon was a funhouse where each piece asked deeper questions about the emerging technology.

For some, VR headsets don’t necessarily mean “more immersion.” While waiting in line for perogies, artist Nitzan Bartov mentioned to me that our literacy in video is more developed than VR, suggesting that watching videos can make us feel just as much (if not more) as being in a headset. Humans are hard-coded for empathy, so no matter how we are stimulated, feelings are inevitable, she tells me.

But when watching videos, I’m only seeing and not doing. Virtual reality frees me from the frame, allowing me to choose where to direct my gaze. In my experience, interactivity is an inherent part of virtual reality, and it can take different forms to elicit weird, new feelings.

An Interactive Gaze

“A sense of presence doesn’t necessarily make you step outside the way you usually look at the world” said Ingrid Kopp, the curator of Tribeca Film Festival’s virtual reality showcase Storyscapes.

360 documentaries distinguish themselves from video because they offer a sense of presence, Kopp suggested that pushing that sense of presence will determine the future of 360 video. She also expressed excitement about the possibility of combining storytelling and game mechanics through VR. “[There’s] something about it being your point-of-view and you wanting to do something with that point-of view.”

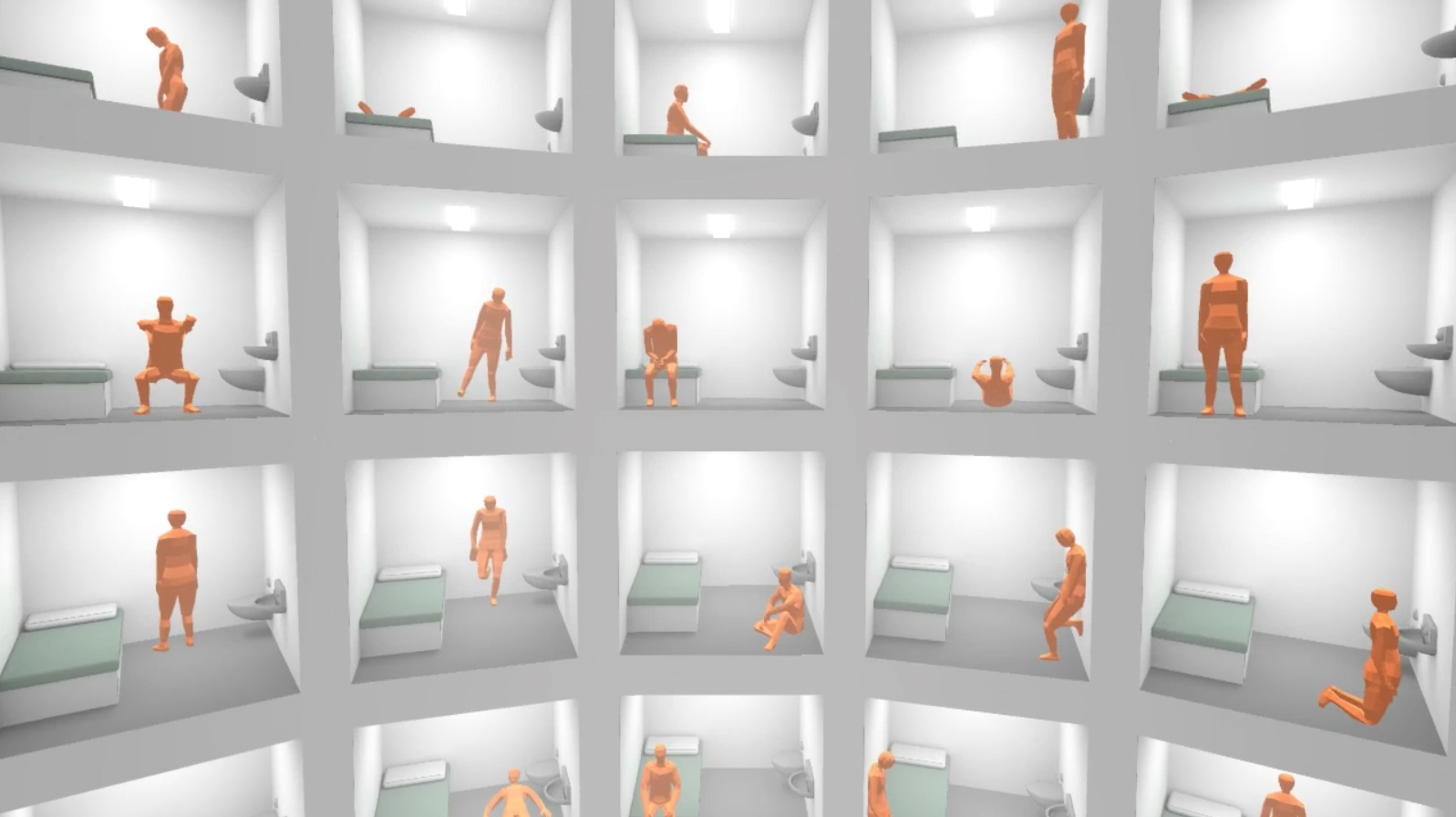

In Molleindustria‘s A Short History of the Gaze you literally use your point-of-view to navigate spaces. Imagine being in the middle of nowhere. You look around and spot a monument in the distance. Suddenly you’re shooting towards it to document it with your smartphone. In another scenario, you’re floating upwards through an infinite cylindrical jail structure where prisoners collapse if you look at them for too long.

Still from the trailer for A Short History of the Gaze. Image courtesy of Molleindustria

To better understand the function of interactivity in VR, I met up with Yasmin Elayat and Alexander Porter from Scatter: a Brooklyn-based collective whose work interprets the social implications of emerging technologies.

Scatter teased its upcoming VR experience Blackout which transports you into the memories of strangers on the New York City Subway. “We want people to have the agency to choose how they navigate and how they want to experience it,” Elayat told Waypoint. “It should be a dialogue, not a one-way storytelling machine.” The work is an example of how interactions in virtual reality can affect behavior in the physical world. “We’re not trying to dictate how people feel, it’s more about setting up a scenario,” said Porter. “Our hope is that people leaving the experience ask questions that they wouldn’t otherwise, [and] listen closer than they would otherwise.”

It was encouraging to see a VR panel not dominated by tech bros. Contexts and Conditions for Independent World-Making Panel at Weird Reality. (L to R) Angela Washko (Panel Chair; CMU School of Art), Jax Deluca (National Endowment for the Arts), Ingrid Kopp (Tribeca Film Festival), Winslow Porter (Independent Producer), Kelani Nichole (Transfer Gallery), Jason Eppink (Museum of the Moving Image), Lauren Goshinski (Co-Director, VIA Festival; co-curator, Weird Reality). Photograph by Hugh “Smokey” Dyar.

The feeling of taking off a headset is like waking up from a dream and remembering everything. Memories created in virtual worlds can link with our personal realities. A virtual shopping experience called Ditherer by the Institute of New Feeling puts you in a towering IKEA-style warehouse where picking up an avocado transports you to the mythical origin of the fruit in your hand.

Your decision to engage with the avocado in virtual space creates a memory that changes your relationship with potentially all avocados. Now, everytime I pick up an avocado, I remember the warehouse collapsing before my eyes and a sunny Jeep trail unfolding in a Mesopotamian landscape.

The Impossibility of Presence

Conveniently located next to the bar, I discovered a VR pregnancy simulator. It was a demo by the startup Preterna, created by Kristen Schaffer and Jeremy Bailey. On trying it, I found myself in a lush field reminiscent of a Windows XP wallpaper. My hands were tracked with a Leapmotion attached to the headset. But as my virtual hands rubbed my new baby bump, my real hands felt nothing. In this disconnect, the satire of the work was evident.

“That’s the whole thing about it—you can’t be me pregnant,” Schaffer told me later. While her body was 3D-scanned and manipulated to look pregnant, she wasn’t actually pregnant—and neither are you. The work highlights the suspension of belief necessary to trick yourself into feeling present in virtual reality. New media theorist Wendy HK Chun summed up this sentiment succinctly in her keynote: “If you’re in someone else’s shoes, you’ve taken their shoes.”

A creator’s authorship over what someone feels is limited because everyone introspects in different ways. But allowing for decision-making in virtual reality lets creators use players’ introspective mindspace to have a conversation with them.

Preterna emphasizes both the ability and inability of VR to transport a user from their own body. GIF courtesy of

The Digital Musem of Digital Art (or DiMoDa for short) takes the introspective museum visit into virtual reality. I took a break from the event to speak to the DiMoDa crew on Telegraph Hill. “It’s the opposite of brick and mortar museums,” said its creator Alfredo Salazar-Caro, “In simulations you can really make anything happen.”

Its second iteration DiMoDa 2.0 had portals to four experiences, one of which was Miyo’s War Room by Miyo Van Stenis. The DOOM-inspired game puts you in a world laden with pastel military tanks and shadowy monsters frozen in time. You find a weapon and approach a futuristic brothel filled with what DiMoDa’s curator Helena Acosta described as “philosophical prostitutes”—the only sight of life. “You’re pushing the viewer,” Acosta said. “It’s creating this odd situation where you’re forced to have a reflective moment that brings your political reality into the game.”

But to assume that virtual reality will bring a universal emotional revolution is a mistake. In November, when VR journalist Nonny de la Peña’s acclaimed piece for the World Economic Forum titled Project Syria went up on SteamVR, it gained mostly negative reviews and angry (occasionally racist) comments accusing her of spreading propaganda. Although successful on large humanitarian platforms, the piece was attacked by gamers on SteamVR. Intended audience and actual audience will always be important factors.

Although it’s impossible to simply create empathy from thin air by strapping a headset on your face, virtual reality can offer us a safe, introspective space away from the physical world. Weird Reality showed me work that created a dialogue through VR’s inherent interactivity, where the creator and player can meet to build something new. Rather than providing me with answers, it let me ask questions. And instead of letting me escape into fantasy, it put me in situations where I confronted my own reality.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Embark -

Samuel J Coe/Getty Images -

Pokemon GO's Holiday Part 1 event 2025