It’s a bit of painful irony, but our best chance at saving much of our computing history involves a few thoughtful souls who thought better of throwing away their physical junk mail back in the day.

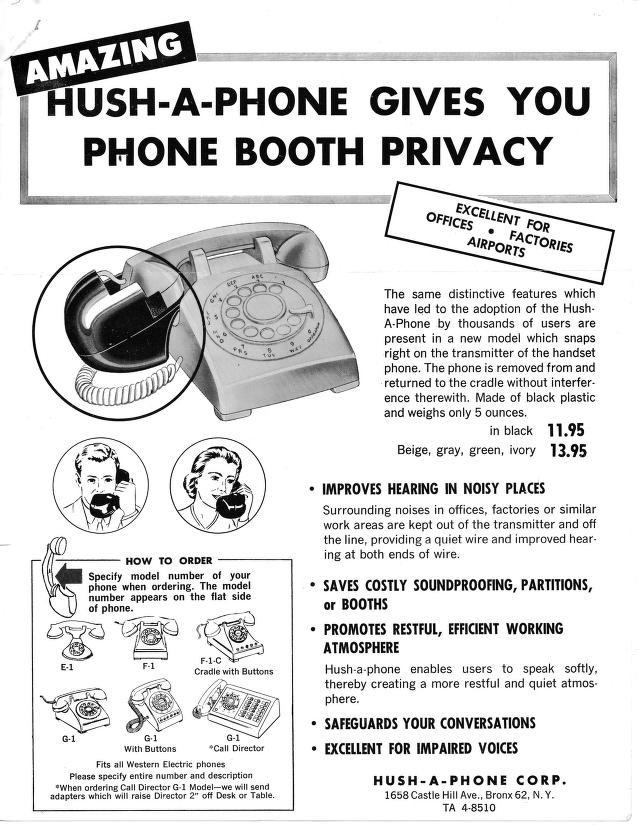

It just turns out that one of those guys is Ted Nelson, the early computing icon who gave us the concept of hypertext and whose thinking had a deep impact on the IBM PC. He was also a bit of a packrat—in a good way. He signed up for random mailing lists and received all sorts of random stuff in his mailbox—like this pamphlet for a Hush-a-Phone, a phone-covering device meant to add privacy to calls.

Videos by VICE

Most people would throw it away. He not only kept it, but he preserved it in good quality.

And because of Nelson’s foresight, the internet gets to see the benefits. In recent weeks, the Internet Archive has been pushing Nelson’s old junk mail online, in part because kindred spirit (and Internet Archive employee) Jason Scott, who was helping organize Nelson’s archives, realized that Nelson’s reasons for keeping this junk mail were very similar to his own archival efforts over the years.

“Ted, basically, did what I was doing, but with more breadth, more variety, and with a few decades more time,” Scott explained in a May blog post.

Kevin Savetz, an online publisher and podcaster with a taste for such archival work, was a bit overwhelmed by the sheer amount of junk mail in Nelson’s collection—Nelson had saved 18 boxes worth of material, each filled with hundreds of pages of direct mail advertising.

“But once I saw some early pictures of files, I was in,” Savetz told me in an email. “It was clear that these documents were special, the collection was vast, and most of it had probably never been preserved.”

And word is, there may even be more boxes somewhere, according to Savetz.

“Ted collected a wide variety of materials. There are flyers for film and video equipment, TV tubes, scientific equipment, computer hardware and software from mainframes to micros, business forms, it goes on and on,” Savetz added. “There are even 50-year-old samples of bubble wrap, which also got scanned.”

An inbox full of surprises

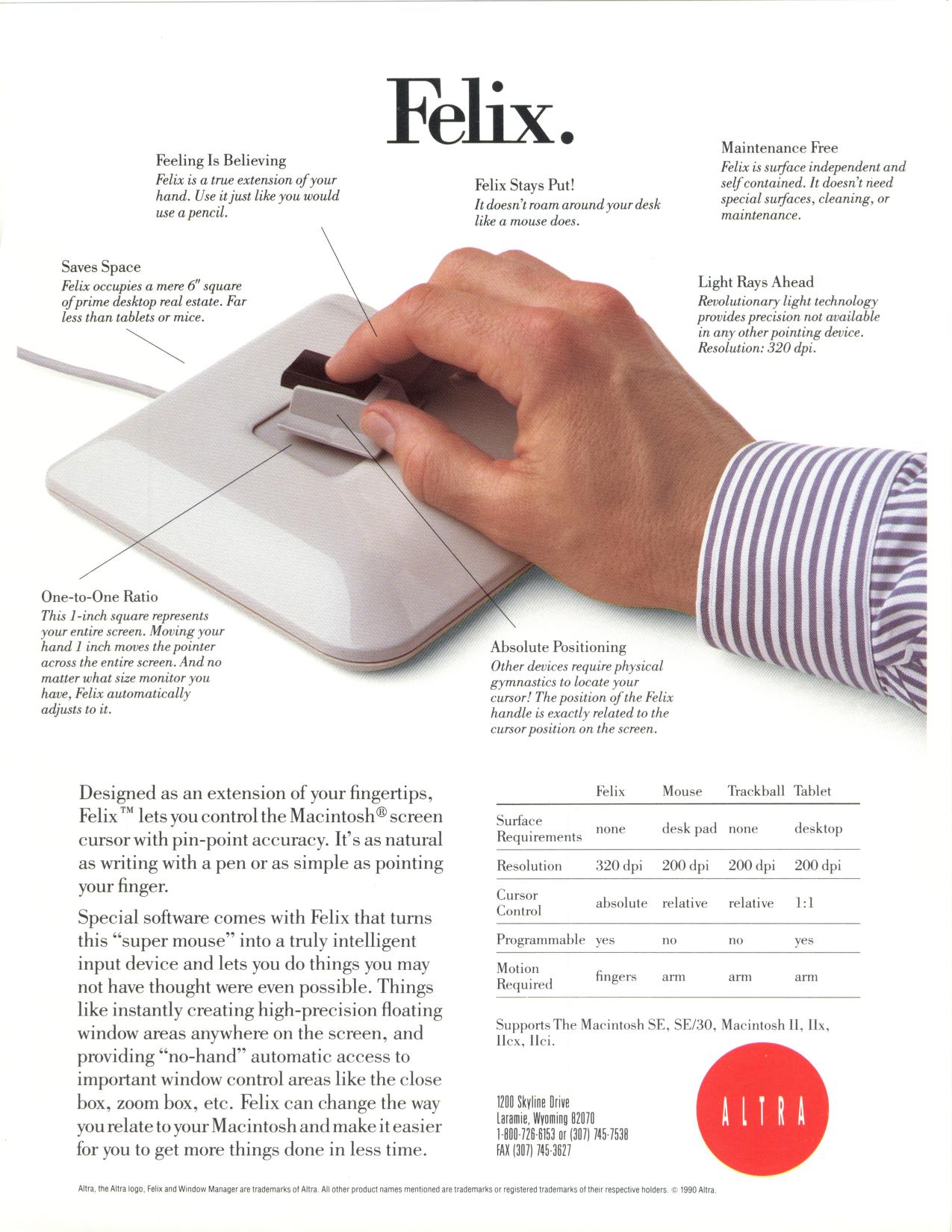

Some of the things hiding in these boxes add new wrinkles to stories I’ve already been fascinated by, such as this pamphlet for a Packard Bell TV camera, or this catalog of early power strips. Others show early memories of companies that have only grown in prominence since they sent Ted Nelson a piece of junk mail, like the microphone company Shure. Others feature advertisements for obscure objects whose history has been forgotten about, or obscure companies serving niche needs.

“One thing that has surprised me in the number of little companies, startups in the ’60s, ’70s, that most of us have never heard of,” Savetz said of the numerous ads in the boxes.

Savetz says there’s so much weird stuff in these boxes that it would be overwhelming to post it all, though he has his favorites—particularly this Broderbund Software info packet from the early ’80s, this catalog for a payroll system, this ad for a four-day seminar on vintage programming languages, and this photo of a device called a Bit Banger, which is literally just a foam mallet you use to smash computers with.

This stuff might not have even found a home in a library at the time it was published. Much of it was marketing material, not designed to last more than a few months. But because these documents have managed to stick around in Nelson’s storage bins, they’ve become objects of genuine historic value.

“It’s just fun to browse, looking at descriptions of technologies that fall somewhere on the spectrum from forgotten to obsolete to perfectly obvious,” Savetz added. “But I can totally see this material being a huge asset to researchers, historians, and students.”

Challenging but rewarding work

Digitizing junk mail and throwing it into the Internet Archive sounds like no big thing, but you’d be surprised at how much work is actually involved.

The work is, by definition, manual labor. Each document has to get scanned using a flatbed machine, at high resolution. And while the archive can use temp workers to help scan in those documents (at a rate of 500 to 600 pages per day), there’s only so much they can do to speed things up. One thing did help, however: Savetz, who handles the quality control, says that he started with a machine that could scan in an individual page in 27 seconds, later upgrading to one that could do the scanning in 13 seconds.

While it’s a lot of work, it’s fortunately very interesting work.

The death of junk mail?

What’s perhaps most fascinating about these well-kept pieces of ephemera is the fact that literally none of this stuff would be advertised in quite this way today. They reflect an era in which things were advertised using glossy manuals, custom-published magazines, and printed documents—all things that the internet has mostly replaced.

Printing is expensive, especially in high-quality, full-color form. Why advertise a piece of software or hardware using a manual when you can drop a few pictures onto a website—a site that may be harder to document than the printed objects that it replaced?

Savetz noted that this is a genuine concern for historians.

“So many companies today get by just fine with a web site—no printed pamphlets, no samples to ship, not even printed press releases,” he told me. “The move to digital makes perfect sense, but I feel like we’re depriving someone 40 or 50 years from now from the joy of seeing and handling physical ephemera that describes this time.”

The next Ted Nelson may not be saving these objects in physical form—because those objects, for better or worse, have already been digitized.

More

From VICE

-

Martin Ruegner / Getty Images -

(Photo by Larry Radloff / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images) -

danirom / Getty Images -

Screenshot: ABONICO GAME WORKS